Bolaño's Voyage:

Bolaño's Voyage:

"Last Evenings on Earth"

Donald Long

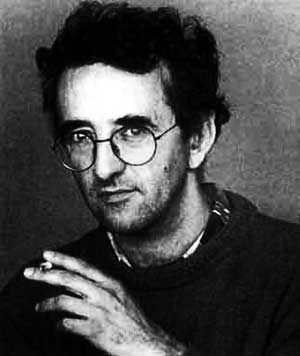

Roberto Bolaño has exploded on the literary horizon worldwide since his early death at 50 of liver failure in Barcelona five years ago. Since then, his ten novels and four short-story collections have been or are being fervently translated in a spectrum of languages. His oceanic posthumous novel 2666 will be out in English this year, 1200 pages of a dangerous and tragic symphonic movement whose crescendo takes place in Santa Teresa, the fictional counterpart of Ciudad Juarez, Mexico. It's across the border from El Paso, and as I drove through it with my family to Chihuahua in late fall of 2006 we looked straight ahead. Flanking the highway tall pink crosses rise from the stony desert floor, testimony to the unsolved murders of over 400 women of all ages. They are at the painful center of Bolaño's last novel. Today, having read much of Bolaño's fiction and having seen the powerful stage adaptation of 2666 at Teatre Lliure with my good friend and literary critic Jaime Morales, I would definitely not wander in the grim back alleys searching for local color but stick to the well-lighted main artery leading south.

An indication of Bolaño's global sweep is that Ken Weeks, a.k.a. Red Winestain, a longtime painter friend and fellow reader living in the forest of remote southern Washington, first put me onto Bolaño last March with an e-mail to Barcelona, attaching Daniel Zalewski's New Yorker essay "Vagabonds". Then, after returning to Oregon, I learned that our friend Rafael Gallardo, a flamboyant Venezuelan painter who exhibits in the competitive Barcelona art scene, is a fan of Bolaño's and reads him in English and Spanish. Bolaño's prestigious and prize-winning novel The Savage Detectives propelled him to the summit of stardom. He was an often fiery but always natural Latin American writer from Chile, an exile in Mexico and for almost three decades, Spain. He is hot with a success h e would disdain, as he did bourgeois respectability and primping for attention, muscling aside the older established stars, García Márquez and Vargas Llosa among them.

e would disdain, as he did bourgeois respectability and primping for attention, muscling aside the older established stars, García Márquez and Vargas Llosa among them.

The short-story collection recently out in paperback, Last Evenings on Earth, is a solid introduction to Bolaño's narrative skill, a unique current that surges through his prose in the tightly restrained short simple or compound sentences, staccato rhythms that illuminate character and scene. The translator Chris Andrews assuredly captures the essence of his style. Here in the title story B., a stand-in for Bolaño and his life's trajectory in time and space, carries the point-of-view. This scene is in a bar outside Acapulco, and B., the son, 22, and his father, 49, are on a brief holiday in a 1970 Ford Mustang from Mexico City:

The door to the patio opens and a woman in a white dress appears. She's the one who gave me the blow job, thinks B. She looks about twenty-five, but is probably much younger, maybe sixteen or seventeen. Like almost all the others, she has long hair, and is wearing shoes with very high heels. As she walks across the bar (toward the bathroom) B. looks carefully at her shoes: they are white and smeared with mud on the sides. His father also looks up and examines her for a moment. B. watches the whore opening the bathroom door, then he looks at his father. He shuts his eyes and when he opens them again the whore is gone and his father has turned his attention back to the game. The best thing for you to do would be to get your father out of this place, one of the women whispers in his ear. B. orders another tequila. I can't , he says. The woman slides her hand up under his loose-fitting Hawaiian shirt. She's checking to see if I have a weapon, thinks B.

The tension builds toward a climactic showdown, like a downed high-voltage wire sparking and flailing in a black night before striking the fatal contact.

The collection of 14 stories is equally divided between two books published in 1997 and 2001, Llamadas telefónicas and Putas asesinas. Usually the point of view is presented through a first person narrator, or B., or Arturo Belano, and the voice is laid-back in leisurely prose, dialogue and narrative woven together without quotation marks, punching the story forward. In "Anne Moore's Life" we follow the peripatetic adventures of Anne from birth in Chicago to middle age in Berkeley, her serial sexual affairs in the U.S., Mexico, Asia, Europe, Africa and Barcelona, where the narrator finally meets her. He reads her 34 notebooks, diaries of a wandering, aimless existence that we have been privy to up to this point through the narrator, who now takes over as storyteller: “During the months when I didn't see her, Anne went travelling in Europe and Africa, had a car accident, left the technician from the machinery-importing firm, saw Paul and Linda who came to visit, started sleeping with an Algerian, developed a skin condition on her hands and arms caused by nervous tension, and read several books by Willa Cather, Eudora Welty, and Carson McCullers.” This 30-page story quietly fades out with one of Bolaño's favorite exit lines, often appearing in other stories, "and then I never saw her [or him] again". The narrator is a detached spectator watching Anne's life unfold over the decades, for better or worse, and Bolaño's tone in this instance hasn't a trace of irony or the implication of a moral judgment. It is up to the reader to draw the conclusions.

At the core of the story "Sensini" are the horrors of murder and torture in Argentina under the military regime, but the surface quietly establishes a deep epistolary friendship between the narrator and an Argentinean writer in exile, who encourages him to pursue the prize money at stake in literary competitions. The setting is Catalonia, and in fact Bolaño did set aside poetry and write short fiction in the 1990s with this aim in mind and the goal of providing more adequately for his wife and newborn son. The darkly tragic tone remains the dominant one throughout the story. In a poignant scene between the narrator and Sensini's daughter in the last two pages, however, it suddenly switches back to the short story competitions both writers were engaged in, and takes on a humorous tone, which in turn brings the daughter and narrator close together. It is a peaceful resolution of loss and of self-awareness, whose import the reader is left to ponder.

Last Evenings on Earth reflects the varied range of Bolaño's fictional world, his shifting narrative styles, and the multifaceted themes that govern his work. The reader is always called upon to become involved, to go beyond the ending, to create his own meaning. The provocative and frustrating insistence on leaving the reader without "closure" is a contemporary technique found also in Cormac McCarthy's No Country for Old

Men.

II

The last stories and essays of Bolaño were published posthumously in 2003 with the title story "El Gaucho insufrible," and "El Viaje de Alvaro Rousselo,t" appearing in The New Yorker in 2007. One of the essays, "Literature + Illness = Illness," is divided into 12 sections, and dedicated to "my friend Victor Vargas, hepatologist." Here, Bolaño mixes humor and irony in astonishing down-to-earth passages that reveal his tough philosophical stance during his last months of hospital visits before his death. He was third in line for a liver transplant. Sex, travel and books (Literature) are subjects central to this essay. Recalling the film "Dead Man Walking" where Bolaño infers that the nun Susan Sarandon reproaches Sean Penn for thinking of making love when his remaining days are numbered, Bolaño comments: "To fuck is the only act that those who are going to die wish for. To fuck is the only act that those who are in jails and hospitals wish for. Those who are impotent only desire to fuck....It's sad to have to admit it, but it's true." In the section "Illness and French Poetry," he turns to literature from film to make his case, citing Mallarmé's poem "Brise Marine," zeroing in on the first line: "La chair est triste, hélas, et j'ai lu tous les livres." In characteristic fashion, Bolaño interprets this line and the poet's subsequent lines on escaping through travel. "But what does Mallarmé mean when he says that the flesh is sad and that he has already read all the books? That he has read until satiated and fucked until satiated....That to fuck and to read, when all's said and done, results in boredom and to travel is the only escape? I believe Mallarmé is talking of illness, the combat that illness wages against health, two states of being you could call totalitarian. I believe Mallarmé is talking of illness cloaked in the rags of boredom."

Bolaño begins the section "Illness and Travel" with an autobiographical sketch of his own travels, from Chile to Mexico at fifteen, and the multiple illnesses he endured in subsequent and constant travelling, "abusing reading that obliged me to wear glasses....abusing sex but never contracting a venereal disease....the loss of my teeth for me was a kind of homage to Gary Snyder, whose life of a zen vagabond made him neglect his dental hygiene." To this litany one could add the abuse of alcohol, drugs and heroin, but after these long years of travelling, "long walks without rhyme or reason," there comes a settling down and life changes: "But everything arrives. Children arrive. Books arrive. Illness arrives. The end of the voyage arrives." There is not the slightest trace of regret or self-pity in this account.

Bolaño becomes more philosophic and cynical in the section "Illness and a Dead-end Alley," quoting at length from the French symbolist poet he most admired, Baudelaire, in a critique of "Le Voyage," "the most lucid poem of the entire 19th century." As the tone changes we are well-aware of the personal impact of the poem on Bolaño: "The voyage that the crewmen undertake in Baudelaire's poem resembles the voyage of the condemned. I'm going to travel, I'm going to lose myself in unknown territory, to see what I find, to see what happens....The voyage, this long and accidental voyage of the 19th century, is like the trip the patient makes on a stretcher, from his hospital room to the operating room, where beings with faces hidden behind masks are waiting, like bandits from the Hashishin sect." And finally this stanza:

Bitter knowledge that the voyage offers!

The world, small and monotonous, today, yesterday,

Tomorrow, everyday, gives us our image back:

An oasis of horror in a desert of boredom!

Bolaño says of the last line, "There is no diagnosis more lucid that expresses the sickness of modern man. In order to get free from boredom, to escape the dead zone, all we have at hand..... is horror, that's to say evil." Here we have the reverberations of Conrad's Heart of Darkness, and Kurtz's cry "the horror, the horror!", that Marlowe witnesses on a devastated and airless oasis. Here we remember the last line of Malcolm Lowry's Under the Volcano: "Somebody threw the dead dog after him down the ravine," and the pervasive feeling of evil in the Farolito bar that foreshadows the Consul's death. And finally we see the row of crosses in Santa Teresa and imagine the streams of blood that have now sunk deep into the sandy desert soil. Roberto Bolaño takes us on this dark endless night of a journey in 2666, The Savage Detectives is a delirious and exuberant tour de force, and his other novels and short stories reveal his extraordinary range and electric narrative power. He writes with a dangerous edge, as close to the abyss as he can get.

![]()

NOTE: For further exposure to this unique and impressive writer, see four fine critical and biographical studies:

The New Yorker: Vagabonds: Roberto Bolaño and his fractured masterpiece by Daniel Zalewski

The New York Review of Books: The Great Bolaño by Francisco Goldman

London Review of Books: In the Sonora by Benjamin Kunkel

Natasha Wimmer's Introduction to her translation of the 2008 paperback edition of The Savage Detectives

© Donald Long

email the author

This article may not be archived, reproduced or distributed further without the author's express permission. Please see our conditions of use.

The Barcelona Review is a registered non-profit organization