![]()

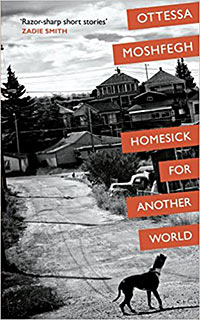

Homesick for Another World

by Ottessa Moshfegh

Jonathan Cape, 2017

Ottessa Moshfegh, author of Eileen, 2015, short-listed for the Man Booker Prize, has given us a collection this year, with many of the stories originally published in the Paris Review. The characters are rough, difficult, often crude, unpredictable and hard to let go of once we enter their world. Take the school teacher in "Bettering Myself," who works in a Ukrainian Catholic School in the East Village, evidently not one so demanding in teacher requirements. She is often still drunk from the night before and between classes frequently naps in a sleeping bag she keeps in a cardboard box in the back of the room. "Most people have anal sex," she tells the students. "Don't look so surprised." And then one day, as can happen, things take a turn as she deliberates what size Diet Coke to order in McDonald’s.

In "Mr. Wu," the single and solitary Mr. Wu spends his days in a video-game arcade, painfully in love with the woman at the counter, who he knows from the neighborhood. He decides to secretly text her to maybe get something going: "How does it feel to be a middle-aged divorcée living with your retarded nephew and working in a computer cafe? Is it everything you ever dreamed of?" Which indeed provides an opening.

The young man in "Malibu" lives off his uncle and doesn't much care to live otherwise. As the uncle says, "All he did was talk on the phone or eat. He loved game shows and cooking shows. I'm not saying he was an idiot. He was just like me: anything good made him want to die. That's a characteristic some smart people have." This line could apply to the array of odd and offbeat characters that fill the pages. They seem bent on wrecking their lives, blithely floating along, emotions numb.

And they lie: "He beats me," a woman tells her concerned neighbor, referring to her boyfriend. a guy who probably "never experienced any real joy or humor . . . . Maybe he was the man of my dreams."

Then there is the married businessman who retreats to the empty family cabin, but is soon interrupted by a knock on the door from a young woman looking for his ne'er-do-well brother, who has "zero ambition" and whose friends "lived in actual trailer parks." He lies to the girl, telling her he's homosexual and that his brother is coming. Why? He has no idea, doesn’t have a clue.

Other characters speak of only being at peace in the "dark and cold." Or, says another, when locked in a room with his girlfriend, "We're in a vortex. We're in a black hole. We've always been in it." And that, too, sums up many of the people in this collection.

The characters may not experience much joy, but humor abounds. One of the funniest is "The Surrogate" where a woman takes a job in a Chinese company as a "surrogate vice-president." All she needs to do is dress the part and pretend. In her off time, when she goes clubbing or to after-parties, she likes to wear a trench coat with a lacy red teddy underneath, snipped in the crotch to accommodate abnormally swollen genitals, with a photo of Charlie Chaplin's face taped on her pubis.

These characters may not win points for empathy or common decency, but those traits are just what they're running from. As one character says: "I feel it is a mistake to look for love in these normal people. They're too neurotic. They aren't capable of love, only of comfort and equanimity."

And who hasn't shared that feeling? In the end, despite all the bleak zaniness, one relishes a certain purity in the rawness as all facades are seared away. There are no sudden epiphanies here, no growth of character, only broken people who may not understand what drives them, but who embrace their foilbes. Ottessa Moshfegh is the real deal; her prose strong and purposeful. Don't miss this one. J.A.

© 2017 tbr

This review may not be archived, reproduced or distributed further without the author's express permission.

Please see our conditions of use.

The Barcelona Review is a registered non-profit organization