![]()

94

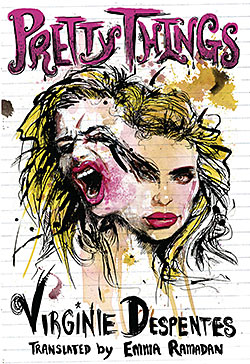

Pretty Things

Pretty Things

Virginie Despentes

translated by Emma Ramadan

Feminist Press 2018

Virginie Despentes is a legend in France, especially among young women. Much of this reputation rests on her first novel, Baise-moi (1994, later made into a film), about a pair of young women, Nadine and Manu, one a prostitute, the other a porn star, who go on a killing spree across France. But she is best known for her 2006 publication King Kong Theory : a feminist manifesto which draws on her own experience of rape and working as a prostitute, to critique the fraught relations between men and women, sex and power and violence.

Published in France in 1998 (Les jolies choses), it is only recently that an English version of Pretty Things has come out ( Feminist Press 2018). In those twenty years, the demands of so-called Second Wave feminism seemed to take a back seat. But in the light of such movements as MeToo in the last few years, Virginie Despentes has gained new recognition and a wider readership. Her novel sets forth, in fictional form, some of the themes of King Kong Theory, sadly still so relevant today.

The story is ostensibly a sort of “a star is born” or “changing places” tale, yet it is anything but a gloopy romance. The “pretty things” refers both to the protagonists and the shiny baubles that success in the trash-pop world can bring—if you play the game.

Briefly, the story concerns twin sisters: one pretty—Claudine the “perfect doll”, with her curvy body and tight clothes; the other—Pauline—the talented one. Claudine hopes to fool her record producer by using her sister’s great voice in order to make some cash. When Claudine commits suicide, Pauline decides to take on her identity and make that hit album. She succeeds, but by the end of the book the once naïve-but-honest country girl seems to have compromised her integrity. Having made herself into a “pretty thing” for the consumption of pop audiences and certain powerful men in the industry, her return is—what? The power to buy pretty things?

In “This Sex Which is Not One” (1985) the French feminist philosopher Luce Irigaray investigates what she calls “the masquerade of femininity” and in Pretty Things we see this process as Pauline “learns” how to assume the trappings of a pop princess: “She thought you either had femininity or you didn´t; she didn´t realise it could be manufactured”.

The part where she practises wearing high heels, staggering around the apartment till she´s mastered the “art”, perplexed by the advice in glamour mags, astonished by the array of potions and lotions in Claudine´s bathroom, are hilarious. When she finally has the confidence to strut her stuff in the street, she sees herself reflected in the desiring glances of passing men and glimpsing herself in a shop window she muses, appalled: “no girl is like that”.

Is this masquerade in fact a sort of female “empowerment”, a free expression of female sexuality? A certain strand of 90´s feminism declared “yes” —with its Wonderbras and pole-dancing classes. And those MTV videos! Endlessly pumped out on screens in cafes and bars. All that Blonde (and Black) Ambition. Madonna, very much her own agent, and let’s suppose it was indeed Shakira and not her producers who decided that slithering around in motor oil was erotic. But what about Britney? Or Miley, twerking away… And, back to the 50s, in another genre, the mother of blonde masqueraders : sad, fragile Marilyn. How empowered are they?

Inevitably, the link between sex and power raises its ugly head in the novel—and it´s not a pretty thing. A visit to a swingers´ club, with its writhing limbs and guttural groans is like a scene from Bosch´s Hell.

To further her chances of getting an album recorded, Pauline has sex with the Big Boss, a much older man who, in order to enjoy sex, “has to viscerate (women) a little in order to debase them.” Of course, they “adore it”.

As for Pauline, “she acquiesces, she swallows it”. She is not portrayed merely as a victim; at times she even enjoys her power to exploit. When a porno video made by Claudine comes out—the Big Boss is scared the scandal will ruin his star´s wholesome image, but Pauline says they should “own it”. Is this a measure of how corrupt and cynical she´s become or an example of a plucky New Woman taking control? That´s for the reader to decide: there´s an intriguing ambiguity in the novel as to this question.

Pauline´s disgust is also, increasingly, with herself: she´s doing this to get what she wants, right? Visits to luxury restaurants, pretty clothes, cocaine…Waiting to get not one but two new checkbooks in the bank, she looks on impassively as a poor woman is denied credit.

There are sweeter moments that lighten the spiralling degradation of the last sections of the book. The scenes where she plays video games with Nicholas, Claudine´s former producer, have a playful, innocent feeling: maybe friendship between men and women is possible. And as her metamorphosis into her dead twin´s role becomes complete, we glimpse a certain sadness and regret when she wonders: “Did Claudine feel powerless, seeing herself shatter into a thousand pieces?”

The novel ends rather abruptly—there´s certainly no “closure”, no easy moral. It seems that in this power play between the sexes, Pauline and Nicholas have swapped places, now that she is rich. He toys with her offer to take the money and run, sweeping him off to Dakar. Dakar! Not Rio or Phuket or some other rich white person´s paradise…

We could read this as a bold middle-finger-up gesture, as two young people flee the corruption of the Paris music business. Or picture it like a scene in a nightclub at 5 am, when the lights come on, the the fizz has gone out of the champagne, the glamourous people have left and there´s only an immigrant worker—maybe from Dakar —sweeping the littered floor.

I tend towards the latter.

review by Roxanne Rowles

© 2019 tbr

This review may not be archived, reproduced or distributed further without the author's express permission.

Please see our conditions of use.

The Barcelona Review is a registered non-profit organization