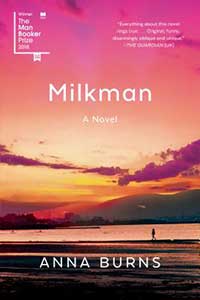

Milkman

Milkman

Anna Burns

Faber & Faber, 2018

I am a bit late in coming to Anna Burns’ 2018 Man Booker prize-winning novel, but so glad I did. Recently, in talking to some teenagers in the U.S., I realized they knew hardly anything about the historical setting of the novel. It occurred to me, too, that the common aggressions against women might seem puzzling. This was an epoch like no other, and Burns pulls us right into the heart of it.

Milkman is set in Northern Ireland in the late 20th century during the time of the Troubles, where car bombings and murders were commonplace. It was a time of both rampant rumor and utmost secrecy. “I felt unease that someone was listening, someone watching, someone following, someone clocking everything, no matter where I was, what I was doing, who I was with . . . .,” says our 18-year-old nameless female narrator, who dares not even name the city (Belfast perhaps) nor the warring sides (tagged by her as “over the water” versus “over the border”; and “our side of the road” versus “their side of the road”). Even her family assumes such names as “wee sisters,” “middle daughter” (herself), “first brother-in-law,” etc. And then there is her “maybe-boyfriend.” Maybe-boyfriend is a car enthusiast and so is thrilled when he acquires a supercharger from a Blower Bentley. But then someone espies a flag decal, a flag from “over the water,” and rumors about maybe-boyfriend take hold, for the narrator’s district was one where the “renouncers-of-the-state were assumed the good guys, the heroes,” although our bright-beyond-her-years narrator is capable of seeing “the inner contraries, the moral difficulties” inherent in the conflict where everything – a child’s name, the brand of tea one uses, the shops one visits – carries political weight. The hospital is off limits as it is a state hospital, and “The only time you’d call the police in my area would be if you were going to shoot them.”

The voice of our young narrator is idiosyncratic, such as seen in a reference to someone who “had suicided” or someone else who “has gone off to suicide.” Her character is equally peculiar. She is known as the “walking-while-reading” girl, Ivanhoe being a favorite as it’s not set in the 20th century. She does not want to know what is going on, does not want to be involved. But when a 41-year-old married paramilitary of some status known as Milkman, starts stalking her – on her walks, on her runs – out of sexual interest, rumor spreads that she is his lover, a paramilitary groupie. Even her mother believes the rumors; eventually the whole district buys into it, shunning her for her loose morals; while, against her will, she becomes obsessed with him – is he lurking round the next corner? Following her from behind? Milkman considers the narrator to be his property, someone who must comply with his wishes. He even threatens the life of maybe-boyfriend. As she tells us, “I’d been thwarted into a carefully constructed nothingness by that man. Also by the community, by the very mental atmosphere, that minutiae of invasion.”

There is a group of seven, known as the “issue women,” who try to form a feminist alliance, meeting in the shed of one of the women, which includes a woman “from the other side of the road” until the paramilitaries, who run the city, raid the shed and it becomes too dangerous a place for the one woman. But on the whole, the only thing that seems to bind the women is the rumor mill, and the many male aggressions against them: men having their way, pinching butts, making lewd comments: “‘Your boot,’ they’d say, ‘Your box,’ they’d say, ‘Your suitability for doxiness,’ they’d say. Then: ‘What we’d do to your face if . . . ’ or something like that, and again with their guns and barely contained, often uncontained, emotions, spilling out over the brim.”

In this complex era of multi-conflict, our young narrator slowly comes of age, not without extreme difficulty. There is much delight to be had in the narrator’s unique way of speaking that lends some humor along the way, such as her descriptions of the “beyond-the-pales,” the crazies in the area whose ranks she will join. She does tend to ramble, so an account of her dead father’s depression, for example, runs into 9 pages, but the ramblings link the personal to the political, if somewhat obliquely. It can take a bit of patience, but all in all, it’s a treasure, a touching glimpse into a time and place that not only highlights our narrator’s personal journey but also serves as a powerful lesson about the extreme danger that lurks behind every major political divide. J.A.

© 2020 tbr

This review may not be archived, reproduced or distributed further without the author's express permission.

Please see our conditions of use.

The Barcelona Review is a registered non-profit organization