Jerry Portwood interviews Carlos

Mayor and Eduardo Iriarte, the two Spanish

translators of Tom Wolfe’s latest doorstop, the 676-page I

Am Charlotte Simmons (which is expected to run to well over a thousand pages when

Ediciones B publishes the Spanish translation in April). The English version of the

septuagenarian Southerner’s novel — centered around college life in an elite

university — has already had its share of panning by the critics and was most

recently awarded the dubious honor of the Bad Sex Award by the British Literary Review.

Mayor and Iriarte reveal for The Barcelona Review their guidelines on how to

properly translate "cum dumpsters" and "froshtitutes" into a foreign

idiom as well as the secrets of how the Fuck Patois will function in Spanish.

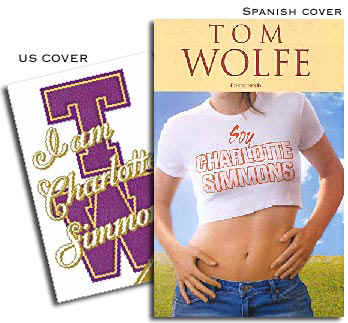

TBR: So, when the book comes out here in Spain, I guess Tom Wolfe’s name will be

pretty big on the cover.

Carlos Mayor: Oh, yeah.

TBR: Are your names going to be on the cover at all or hidden somewhere inside?

Eduardo Iriarte: They’re usually on the first page inside.

TBR: Often translators are kept in the background; you’re supposed to be

invisible. And I wonder if in this process, you have tried to be invisible or . . .

CM: It depends on how big you are. Sometimes you get your name on the title page or on

the cover, but not very often. Probably we’ll get our name on the title page but

usually it’s in small print. I guess that’s something we should have discussed

beforehand.

TBR: How do you feel about that? When you’re dealing with a process like this,

when there’s so much work, you’re creating words and crafting dialogues that are

clearly different from the English version . . . what is your opinion on how visible you

should be?

EI: You have to be invisible, but you can’t always be. I mean, there’s

always a certain sense of style, I suppose. You can’t hide that, even if you aim to.

CM: Right. Sometimes – I don’t really like translator’s notes – but

sometimes, you have to include them. What I really don’t like is to open a book and

get a long translator’s note talking about the process because most readers

don’t want to know that; they don’t even allow the translator to be in the

process.

TBR: But the process of translation is a completely different art form: you’re rewriting

the book. I’m interested in how you are both dealing with Wolfe’s way of writing

and in the process adding to Spanish. The fact is you both have to come up with

words that have never been written before in Spanish. I mean, not only are you trying to

take something from English and translate it into Spanish, but you’re ultimately

changing Spanish in the process.

EI: That’s what’s more difficult in Spanish. English is more malleable?

CM: It’s more flexible.

TBR: Yeah, more malleable.

EI: For example, this always comes up in my work: Maybe in Spanish you have another

technique to say something, but you can’t decontextualize. Or maybe you can use a

word that makes sense in another context, but if you subtly put it in other ways that

aren’t correct, then it sounds too strange.

TBR: You were given a very short time to translate such a weighty book, only a few

months. Is that why you worked together, to share the burden? What kind of stresses come

along with that?

CM: There was no other way. I had to find someone to split the job with. When I was

approached and read the book, I knew I couldn’t get it done in time for the April

publication date.

EI: We split it so that Carlos focused on Charlotte and I focused on

the other three main characters.

CM: I’ve never actually worked jointly on a book before, and I always thought it was

a bad idea because it shows. We wanted to make it look like the same translator all the

way through. Chapters that are viewed through Jojo’s eyes have a different style, for

example, and they have references to other events. So, those are the types of things that

we have had to double-check. The book is all in the third person, but events are

seen through the perspective of several characters. We tried to keep

the style consistent and respect the different points of view despite having two people translating it.

EI: There are certain words, certain motives, for the individual characters, and if

you’re focusing on one character, it’s easier to recognize them.

TBR: I recently read some translations of Cuban short stories from Spanish into

English, and they were so bad. They were all translated by different people and you

could see faults particular to different translators - the grammar, word choice, syntax,

sometimes even the spelling. You really can tell when there’s a translator who is

translating literally or doesn’t have the skills to make it work.

CM: That reminds me, my mother and my sister have been giving me all these books

because I wanted to read more translations of books into Spanish. Sometimes I can hardly

read them because they’re so badly translated. And I asked them, "Didn’t

you notice?" And they said, "No." And I don’t think most people would.

They just think it’s the author’s style. He just writes these weird words and

strange sentences. [Laughs]

TBR: Yeah, that’s true. I could see someone thinking it’s just some strange

stylistic choice, and had nothing to do with the translator.

ED: There are some translators who want to shine too much. You read several

translations by them and you can see their similarities even if there are no similarities

in the original work. I don’t think that’s desirable.

CM: Yeah, while we were translating the book we read one of the essays that Wolfe wrote in

the 70s. It was translated into Spanish a few years later and it was dreadful. The essay

was useful because it talks about his style and a lot of the choices that he makes and

about why he uses punctuation the way he does – he thinks it’s a trait of his

character. The translation was full of footnotes. The translator was a cinema critic and

whenever there’s any reference to a film there would be a note: This film was shown

in Spain with this title, this year. So annoying.

TBR: Where did you study English, Carlos? In England, right?

CM: I studied translation, but afterwards I went back to university and studied

journalism. I had an Erasmus scholarship, so I went to Leeds for a few months. Then I

lived in London for a couple of years. I’ve also lived in New York.

TBR: And you Eduardo?

EI: I went to high school my senior year in the States. Believe it or not it was

Topeka, Kansas. And I went back a few times to spend a summer in New Jersey and was in

Maryland working.

TBR: So you’ve had this more "authentic" American experience than most

people. Not just New York or San Francisco.

EI: I went to New York from Kansas by bus.

CM: And how long did it take?

EI: Well, I stopped a few places, but . . . but three or four weeks?

TBR: That’s something that most Americans wouldn’t do.

EI: Well, I wouldn’t do it now. It was fun then.

TBR: I ask this because when translating you go back and forth between British English

and American English. I notice when you speak, Carlos, you sometimes use British slang or

terms, and I wonder how that influences, if at all?

CM: Well, the more you know about any use of the source language, the better, really.

Also, translating implies a completely different level of knowledge.

EI: I agree. I think the reading that you do is more important. I think apart from visits

to the States or Britain, it is what you have read that really matters.

TBR: I’m assuming the people who are going to want to read the book are doing so

because it’s set in America. Were there problems with cultural references?

EI: American culture is so . . . um [laughs] omnipresent.

CM: We get so much American culture every day. It’s no problem.

EI: We almost always get the references, there are just certain words that don’t

exist, didn’t exist at least in Spanish, and aren’t always common to Americans.

There’s the Fuck Patois, the Shit Patois.

TBR: The what?

EI: Fuck Patois? That comes from the main character Charlotte who thinks . . . what

did we translate that as?

CM: Yeah, the Fuck Patois. Hah. El putañés. Charlotte is shocked when she first

gets to the campus because she’s a prude, I suppose. Well, they say fuck all

the time, which she’s not used to. So, she thinks they are speaking in this dialect

which Wolfe calls "Fuck Patois."

EI: Do you know where that is in the book? [He begins thumbing through the 600+ pages and

it’s obvious they are both familiar with every single page and its content.]

CM: Yeah, there’s also the Shit Patois, el mierdés.

TBR: So she’s supposed to be thinking and using this word "patois" which

isn’t a word most English speakers would normally use.

CM: Well, she’s really pedantic. She’s 18 and she’s just finished high

school, and she’s the brightest in her school.

TBR: The valedictorian, or what?

CM: Two students out of every state are singled out as the best students and they go

to meet the president because that’s so important, of course [he smiles ironically],

and they shake the president’s hand. And she’s one of them from North Carolina.

She’s always thinking about etymology and words in Greek and Latin and thinks no one

else there knows the plural of this or that Greek word. Because, to be correct, you have

to know Greek and no one knows Greek, and, well, she has a really high opinion of herself

which is why she keeps repeating "I am Charlotte Simmons." And she’s

obviously not as clever as she thinks she is.

TBR: How do you go about dealing with something as essential as swear words to the

original language?

CM: Well, one of the problems with "bad language" – as you all call it

in English – is that in Spanish you have so many options for what in English can

usually work with just fuck or shit. But in Spanish there are more words and

combinations of words that would be used in the same context. You can’t just

translate fuck as joder although it’s just one word repeated in so many

different ways, because you have joder, coño, hostia. So you have

many words that you have to use to mean fuck.

EI: In English you can use fuck as an adjective, verb, noun, whatever. Not in

Spanish.

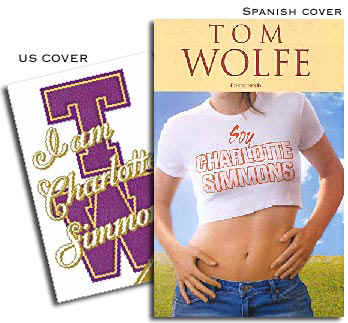

A short

excerpt from Chapter 2: "The Whole Black Player Thing" which introduces the idea

of the "Fuck Patois" and gives a preview of the Spanish translation. |

Without even realizing what it was, Jojo spoke in this year’s prevailing college

creole: Fuck Patois. In Fuck Patois, the word fuck was used as an interjection

("What the fuck" or plain "Fuck," with or without an exclamation

point) expressing unhappy surprise; as a participial adjective ("fucking guy,"

"fucking tree," fucking elbows") expressing disparagement or discontent; as

an adverb modifying and intensifying an adjective ("pretty fucking obvious") or

a verb ("I’m gonna fucking kick his ass"); as a noun ("That stupid

fuck," "don’t give a good fuck"); as a verb meaning Go away ("Fuck

off"), beat – physically, financially, or politically ("really

fucked him over") or beaten ("I’m fucked"), botch

("really fucked that up"), drunk ("You are so fucked

up"); as an imperative expressing contempt ("Fuck you," "Fuck

that"). Rarely – the usage had become somewhat archaic – but every now and

then it referred to sexual intercourse ("He fucked her on the carpet in front of the

TV"). |

Sin ser consciente siquiera de ello, Jojo hablaba el dialecto universitario en boga: el

putañés, en el que las palabras «puta», «joder» y «hostia» se utilizaban, por

separado, combinadas y, por supuesto, aderezadas también con otros muchos tacos, como

interjección («qué hostias» o sencillamente «joder», con exclamaciones o sin ellas)

para expresar una sorpresa desagradable; como adjetivo («puto árbol», «putos codos»)

para expresar menosprecio o contrariedad; como locución adverbial para modificar y

recalcar un adjetivo («es obvio de la hostia»); como verbo («ahostiar», «putear»);

como sustantivo («mecagüen la puta», «no sabes ni hostias»); como expresión

destinada a librarse de alguien («vete a hacer hostias»), a menoscabar en el aspecto

físico, económico o político («lo putearon»), a subrayar el cansancio («estoy

jodido»), a indicar que alguien la ha pifiado («la jodió de medio a medio») o que

está borracho («anda que no estás jodido»), o como imperativo para expresar desdén

(«que te jodan», «no me jodas»). Era poco común (se había convertido en un uso más

bien arcaico), pero de vez en cuando la palabra «joder» también hacía referencia a las

relaciones sexuales («se pusieron a joder en la alfombra delante de la tele»). |

|

TBR: Have you found words that are just not translatable?

EI: Usually you can explain them in the context with a short sentence. You can find a

way around them.

CM: Eduardo was trying to translate "God’s yuccas." We asked several people

to find out what they thought it was. No idea. We eventually realised that the characters

were just shouting something to sound like "cocksuckers." With the internet and

all the research materials available, it sometimes appears as if everything had to have a

background and a purpose. If it’s not in Google, it doesn’t exist. [Smiles.]

While I was translating this, I went to the country one weekend. I was spending all this

time on the translation and I mentioned to a couple of friends that we just couldn’t

figure something out. There was a song in the book that we couldn’t get, and I asked

my friend Richard, who is from Louisiana, if he knew anything about it. He explained that

it is an old song from the South, but a few lines had been changed to make it funnier.

It’s just one of those things that, unless you know it, you’re not going to get.

EI: Most readers won’t understand all the references, but you can explain it or hint

at it somehow.

CM: Normally I read it, try to understand what is meant, then sit down and write it down.

It’s quite important with Tom Wolfe. It’s not always as difficult in this book

as in A Man in Full. You have to decide how you’re going to reflect the

dialect. Are you going to make them speak like they do in English? We decided not to do

that. We didn’t create a new, different dialect.

EI: For the last book the translator created several new dialects in Spanish.

CM: We decided that we didn’t need to do that. We were already doing so much

research, and if you’re creating something new like that, you’re making it up

yourself. I’d rather not make something like that up. It’s not true to

[Wolfe’s] spirit and definitely not real.

EI: Let’s hope critics will like that decision. I’m anxious to see.

TBR: How do you decide on the translation of slang?

EI: I met with some college students, but what they ended up telling me . . . it

didn’t come out quite right, because they were trying to make new words that in a way

didn’t mean anything. And if you use them, then I don’t think they would be

understood.

TBR: What about some examples that you came up with on your own then?

CM: Novuta, that’s froshtitute, it’s only used a couple of times.

EI: Awfucks disease. [They both laugh.]

CM: Yeah, Awfucks disease. That’s when you wake up in the morning next to someone you

had sex with and say, "Oh fuck!"

TBR: What about having to deal with this American style of writing that usually entails

short sentences, a more journalistic style perhaps.

EI: It has to sound right. You read it and it feels that it’s right. It all comes

down to instinct. Sometimes you improvise, but it’s not an exact science.

CM: You want to reflect the meaning, not the words. You have to make it sound Spanish. And

a lot of times Spanish sentences are longer. But I don’t think Wolfe’s sentences

are actually that short. Sometimes he goes on for quite a long time. There are a couple of

pages where you have no punctuation at all and that takes about a whole morning to

translate – finding where things go, in what order.

ED: The reader knows what to expect of Tom Wolfe. I suppose we’ll see if people get

it or not.

C: If it’s something interesting or a specific trait of a writer, you try to keep it

in. There’s the passage where Charlotte has a drink for the first time. She storms

out of the room, out of the house, and there’s a long paragraph with no punctuation,

so that’s actually quite difficult. You have to read it very carefully to know

what’s going on.

EI: You just read it over and over again until it sounds right.

TBR: It sounds a lot like the process of the writer himself.

EI: Except within limitations, because you don’t have that much freedom.

TBR: How do you deal with that, Eduardo, since I know you are a fiction writer as well?

You’ve mentioned not having that freedom, does that make it difficult?

EI: Well, it’s more a matter of responsibility. You have to know your limits. You

always have someone who corrects the translation, and the editor or the publisher who

looks it over. You can’t change that much from the original. And I try to keep my

writing work separate from this, the translations. But it’s not always possible.

Somehow it affects what you write. I translated three books by Charles Bukowski in the

last three years and somehow it always, uh, there’s a … poso. ¿Cómo?

CM: Something like a sediment.

EI: Yes, a sediment. Anyway, it’s always positive, I think. I mean, you can always

learn something about an author even if you don’t like his writing. It’s the

best school for a writer. Everyone says so because you analyze writing so much. It’s

the best reading possible, and you learn what you can use from other writers.

TBR: You’ve mentioned that there’s a certain amount of research that you have

both done, reading of reviews and other background materials. I assume you are aware of

things about the book that certainly the reader isn’t. Is it strange rewriting the

book in Spanish but also with this great awareness of what critics have said? Do you

"correct" it? Do you make it better?

CM: We reread his other two novels [A Man in Full and Bonfire of the

Vanities], checking the translations of the Spanish because we knew that in

Wolfe’s case the translation stands out so . . . And we wanted to see what the other

two translators had done before.

EI: There are those who say the translator has more responsibility sometimes than the

author himself because he knows so much about the book after it’s been written. The

author just writes and then the critics study the book, but the translator already has so

much knowledge of the book, more than the author, and the translation itself carries so

much responsibility for that reason. I mean, when you write, you have all the freedom in

the world. You can choose any word that you want. And then, when you translate, you have

to come up with certain words, and you don’t have the freedom to change that.

TBR: And what about the repetition of things, how Wolfe uses the same words over and

over again?

CM: Right. Everyone smiles in the book. Everyone laughs. Everyone "says"

this or that.

TBR: Yeah, "he says" / "she says." That’s a very normal way of

writing in English because you want to get past those attributions as quickly as possible.

CM: But that’s not the case in Spanish. It was even more of an issue when you

have someone who laughs. Then someone else laughs. Then someone smiles. I mean, you have

other word choices in Spanish and in English. But Wolfe uses smiles, smiles,

smiles, smiles. He wants to make a point because he wants to show that the students are so

stupid. So another laugh, another smile.

TBR: I guess you’re afraid that readers would start thinking these people are

idiots, always smiling and laughing?

EI: The vocabulary is so, so reduced. I don’t think most university students

think like that. I think this is a caricature.

CM: He’s very judgmental in this book. I mean, he has his opinions about the

characters and he wants you to know that.

EI: I think there’s been too much focus on the sex and language. The book is much

more. It’s about education and maybe the future of the United States. And no one says

anything about that.

CM: I don’t think readers in Spain are going to be shocked by the language. Because

it just doesn’t shock people. And there’s really not that much sex.

EI: But there’s THE WORST SEX SCENE EVER.

TBR: What did you guys think of the Bad Sex Award?

CM: I didn’t think the scene was very good. He was trying to make a point, I

suppose. This is Charlotte, who is very prudish, and she has a boyfriend who’s

driving her home and they start kissing and then he goes a little further, not all the

way, and you’re getting what she feels so it’s all very technical and it makes

sense in the context because she’s very, umm . . . I don’t know. I think she

distances herself a lot from things. And she uses lots of words no one her age would use.

So, I think in this case it makes sense, even though it’s in the third person.

It’s seen through her eyes. The chapter’s called "The Hand."

EI: It’s about 30 pages long.

CM: She’s snogging him. She has this guilty pleasure. And she thinks the hand is . .

. it is a bit ridiculous.

TBR: I guess for you it doesn’t really matter about the award or what critics are

saying about it.

CM: It was funny for us because we were working on it. It’s just very clinical,

and he uses this word: otorhinolaryngological. I can’t even say it in English.

TBR: Neither can I. Maybe if you’re a gynecologist or scientist, yeah.

CM: Well, incidentally most Spanish speakers will be able to say

"otorrinolaringólogo". That’s your ear, nose and throat doctor. Anyway,

there’s also something else about the fact that he created words. I think that they

were based on research. He says they were. And he created an explanation for them.

EI: He said that maybe those words won’t be used in five or ten years from now.

TBR: But it took him almost that long to write it, so . . .

CM: True. There’s a note at the beginning to his two children to whom he

dedicated the book [he reads]: "hoping you might vet it for undergraduate

vocabulary," and then he goes on to say he learned from them that "students who

load conversations up with likes and totallys, as in ‘like totally

awesome’ are almost always females."

TBR: Unless it’s meant to be ironic.

CM: Yeah. Like totally.

TBR: I’m not sure how comfortable you’ll be with this question, Eduardo, but

it seems that translators could make the best critics. After being so knowledgeable about

the book’s characters, style and content, do you like it?

EI: [Laughs.] Well, I enjoy it. I enjoyed translating it very much. I think it’s

quite good, actually. But he’s somehow very . . . Somehow too distanced from what he

writes, from college life. I think sometimes it’s a caricature of college life. It

could have been better, I think. I mean, the book as a whole. It could have been more

realistic. Instead of making fun of college life and the students, he could have had a

little more sympathy. I suppose some students or some professors might feel insulted by

it, and maybe that’s what he wants.

TBR: And you, Carlos?

CM: I’m very fond of him. I liked the other two novels more. I really

enjoyed A Man in Full. I think most of the reviews have been based on the way he

looks; what he says. It’s very easy to make fun of him. I don’t think all the

critics are looking that closely at the book. But that’s probably all orchestrated.

It sells a lot more books.

EI: He’s a polemicist.

CM: Yeah. It’s an interesting study of American college life, American youth. He

tells a good story in the book, but doesn’t fully realize the potential in my

opinion. He tries to be detached, but he’s judging all the time. I don’t think

he intended to, but he seems shocked by what he found. He wants a passage to be objective,

but it doesn’t happen that way. And, well, it’s a little bit too long.

EI: Somehow, I thought it was going to be even longer.

[They both laugh.]

|