![]()

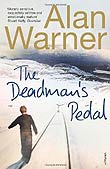

The Deadman’s Pedal

The Deadman’s Pedal

by Alan Warner

Jonathan Cape, 2012 / Vintage paperback 2013

A new offering by Scottish writer Alan Warner (Morvern Callar, The Sopranos, The Stars in the Bright Sky) is always an occasion for excitement. In this latest, winner of the James Tait Black Fiction Prize, we are back in the Scottish highlands with its rainy weather and dramatic scenery, this time following a dual story line set in the 70s which follows a bunch of old timers on the Scottish railway—slowly dying of importance due to cheaper transport by lorry—along with a group of teens just beginning to make their way in life. Sixteen-year-old Simon has one more year of school, but he’s bored and wants to work. Rather by accident, he’s offered a job on the railway (while looking for work at the labor exchange, he mistakenly thought that "trainee traction" might have something to do with hospitals and nurses rather than training to be train driver). One enticement is that he must do training in Glasgow where he can rent a hotel room to have sex with girlfriend Nikki, who lives in counsel housing with her parents and loose older sister, the nurse Karen. Simon’s father is fairly well off, having a large lorry haulage business, and is dead set against his son dropping out of school to work on the railway of all places, but he can’t stop him.

Part of the fun is watching the new young kid mingle amongst the railway workers, most of whom have been there for donkey’s, have their own code and banter, and enjoy teasing and mocking young buck Simon, who, thanks to a quick wit, manages to hold his own.

The book begins with a wake for an old railway worker, attended by his aging colleagues, one of whom is the highly revered John Penalty, a crippled man who Simon will later pair up with in driving the locomotive with its ‘deadman’s pedal’—the safety pedal that allows operation only while depressed by the operator.

Over the miles back and forth, Penalty always told Simon railway stories from

the steam days. How with coal shortages during the war they ran out, and the passengers themselves had once climbed down from Penalty’s train and fanned out into the trees—looking for fallen wood to burn in the firebox so they could reach the station. Once at Fort Junction when they were delayed an hour, an impatient Penatly had stated, ‘Young Fella, I’ll show you what the real railway’s all about,’ and he undid his trousers. Simon got such a fright he backed himself against the side of the cab.

Simon drives the midnight train, getting to know every bend in the road, while on his days off he enjoys riding his motorbike with Nikki until he brushes up against two spoiled siblings from the local aristocracy—the eccentric Alex Bultitude in his ratty Afghan coat and long hair (not typical in the small highland town) and his beautiful, horseback-riding sister Varie—home from their private schools. Their father represents about everything the working class railway crew despises, especially as it was Mr. Bultitude’s greed and influence that wrangled the purchase of a huge parcel of land, necessitating the evacuation of the locals, who were packed off to council housing, in order to create a dam system in which the “Mad bugger flooded the whole glen for the money.” Nevertheless, Simon falls for the charms of Varie, marking the beginning of a clash of social class and conscience, which puts everyone to the test just after a dramatic scene on the railway one stormy night brings the denouement to that thread of the story.

Warner has researched his railway lore well and it is obvious he harbors a love of the profession. His characters—Big Ian the driver, Wee Ian, Hanna the strong Scots unionist and nationalist, Penalty—all come alive and pull you into their world whether it be on the midnight train roaring through the deep forest or a union meeting of hilarious mockery or a table at the local pub. One gets a good glimpse of a way of life—and, I suspect, a type of camaraderie—soon to become obsolete.

Likewise, no one like Warner can capture the longings and vicissitudes of young love with all of its joy and heartbreak (and of course sneak peeks at girlie knickers). It would be easy, given the subject matter, to fall into sentiment and lapse into coming-of-age stereotypes, but anyone who has read Warner knows he writes on a far higher plain. His exquisite prose, often reaching the sublime, is more assured than ever, the music of the Scots dialect falling gently on our ears. I have a piercing desire to visit the Scottish highlands every time I read Warner. He is their chronicler extraordinaire. J.A.

© tbr

This review may not be archived, reproduced or distributed further without the author's express permission.

Please see our conditions of use.

The Barcelona Review is a registered non-profit organization