OTTESSA MOSHFEGH

OTTESSA MOSHFEGH

THE SURROGATE

"This suit will be your costume." Lao Ting pointed to the black skirt and jacket hanging from the coatrack in the corner of his office. "You will tell people you are the vice president of the company. They may see you as a sex object, and this will be advantageous in business negotiations. I have noticed that American businessmen are very easy to manipulate. Has anyone ever told you that you resemble Christie Brinkley, the American supermodel of the nineteen eighties?"

I said a few people had. I did look like Christie Brinkley, and like Jacqueline Bisset and Diane Sawyer, I'd been told. I was five foot nine, 116 pounds, with long, silky light brown hair. My eyes were blue, which Lao Ting said was the best color for someone in my position. I was twentyeight when I became the surrogate vice president. I was to be the face of the company at in-person meetings. Lao Ting thought American businessmen would discriminate against him because of the way he looked. He looked like a goat herder. He was short and thin and wore a white linen tunic and a belt of rope around his beach shorts. His beard was nearly white and hung down like a magical tail from his chin to his pubis. My previous job had been as a customer-service representative for Marriott Hotels, taking reservations over the phone at home. I'd been living in a studio apartment above a Mexican bakery in Oxnard. The view out my window there was a concrete wall.

"Your last name will be Reilly," Lao Ting told me. "Would you like to suggest a first name for your professional entity?"

I suggested Joan.

"Joan is too soulful. Can you think of another?" I suggested Melissa and Jackie.

"Stephanie is a good name," he said. "It makes a man think of pretty tissue paper."

The company, called Value Enterprise Association, was run out of the ground floor of Lao Ting's luxurious threestory family complex on the beach in Ventura. It was a family business and had an old-fashioned quality that put me at ease. I never understood the nature of the company's services, but I liked Lao Ting. He was kind and generous, and I saw no reason to question him. The job was easy. I had to memorize some names, some figures, put on the suit, makeup, use hair spray, perfume, high heels, and so forth. Everybody at the office was very gracious and professional. There was no gossip, no fooling around, no disrespect. Instead of a watercooler, they had a large stainless-steel samovar of boiling-hot water set up in the foyer. The family drank green tea and Horlicks malted milk from large ceramic mugs. Lao Ting's wife, Gigi, gave me my own mug to use, like I was part of the family. I spent a lot of time sitting on the deck, looking out at the sea. It felt good to be out during the day, and to be appreciated. Lao Ting assured me that he would never expect me to engage in unprofessional activities with clients or vendors, and I never did. Everything was handled very honorably.

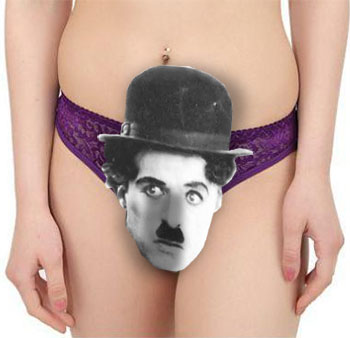

The surrogate position paid six times what I'd been making answering phones for the Marriott. I quickly paid off my credit-card debt and moved into a converted loft in an industrial area of El Rio. I furnished it with rentals and little decorations from gift shops. I was relieved to sell my car, a huge white Cadillac that had been on the brink of engine failure. Lao Ting employed a service to drive me everywhere I needed to go for work, and when I went out to clubs and parties on the weekends, I called cabs. I could afford it. I mostly went to the underground clubs and after-parties downtown or out in the desert. It was a weird crowd—freaks edged out of the LA scene, kinks from the valley, middle-aged ravers, tech rats on acid, kids on E, old women, the usual hustlers. I got dressed up special on the weekends. I liked to wear a trench coat, an old hat like a detective's, and large, tinted eyeglasses. Underneath my coat I wore a lacy red teddy. I'd snipped at the fabric around the crotch to accommodate my genitals, which were abnormally swollen due to a pituitary situation. Underneath the teddy, there were pennies taped over my nipples and a cutout photo of Charlie Chaplin's face taped across my pubis. I felt good wearing all that. Even before I got the job as the surrogate, I felt like normal clothes were all just costumes.

I'd been ashamed to bring men back to the studio in Oxnard because it smelled like a deep fryer, and there was no place to sit but on the grubby carpeted floor or on my bed, which felt too intimate. When I took men home to my loft in El Rio, which I didn't do often, they looked around at my stuff and asked me what I did for work.

"I'm the surrogate vice president of a business enterprise," I'd say. I'd sit them down on the rented couch and give them a clear plastic bag to put over their heads if they so desired. When my swelling was particularly bad, I got a little uptight. "I do not want to make love," I said to one man I remember: He was handsome and tan. He wore white clothes for dancing the capoeira, which is what drew me to him.

"'Do not want,'" he repeated, chortling under the plastic, his eyes sparkling.

"I don't do sex," I explained. "I just want to strip."

During the long cab ride from the club, he'd talked like this: "My work pays for everything—drinks, meals, travel, hotels. I go to Canada all the time. Coffee shops, theater tickets, everything. I get reimbursed," he was saying. "Quote unquote," he said over and over. His hands twitched and his eyes were hot-wired and roving, like there was lightning trapped inside of his eyeballs.

"Tell me something secret," I said to him, unknotting the belt of my coat.

"I have pet bunnies," he said. He sat up straight on the edge of the couch. "White with red eyes. I feed them meat. I feed them tuna." Then again, "While I'm in Canada, quote unquote, a neighbor babysits them, my little babies," and so forth.

Being watched was the only erotic pleasure I could really enjoy. After I removed my trench coat, I took off my shoes. Next, I undid the snaps of the teddy and let it fall to my feet. "I do not want to make love," I reiterated, as I plucked the pennies from my nipples .

"'Do not want'?" the man repeated. "Why do you talk that way?"

"For emphasis," I said. I told him to peel the photograph of Charlie Chaplin off my pubis. He flicked at the Scotch tape with his long, brown fingers. He wasn't in any rush. It was like he had enough excitement happening inside his eyeballs. Maybe, to him, the rest of life was just so-so.

"Who's this guy?" he asked.

"Hitler," I said.

He gasped, and I pulled the plastic bag from his head. "Limos, dinners, dance clubs," he was saying. He yanked at the photograph and my labia tumbled out against my thighs. "Ha-ha," he said, poking. "You have more than meets the eye."

*

Gigi was the operations manager. She helped me with my hair and makeup and prepped me for meetings with the businessmen. We got to know each other pretty well. One time, I told her about my troubles in romance. "I can't engage with normal people," I explained. "When I go to the grocery store, or out for dinner at a normal restaurant, I am frightened. I don't understand how to act. Men pay me attention because of my looks. But I feel it is a mistake to look for love in these normal people. They're too neurotic. They aren't capable of love, only of comfort and equanimity."

Gigi said, "Don't worry about finding a husband. When the woman is the hunter, she can only see the weak men. All strong men disappear. So you don't need to hunt, Stephanie Reilly. You can live on a higher level. Just float around and you will find someone. That is how I found Lao Ting. It was as if there were a spotlight on him and he walked on air about two feet off the ground. I saw him from a mile away, floating down Rego Boulevard. Funny to imagine now, but he was once a very handsome man."

"That's beautiful, Gigi," I said.

"It's a beautiful love story. I will tell you more about it another time."

Value Enterprise Association employed another surrogate to act as my attorney at important meetings. He and I would sit at long glass tables in office buildings in LA, drink ice water, and give the businessmen contracts to sign. Apart from these meetings, communications between the family and businessmen were conducted in writing and over the telephone. Lao Ting and others used the name Stephanie Reilly in their correspondence. Gigi spoke as Stephanie Reilly on the phone. She had a perfect American way of talking and laughing. When the businessmen met me in person, they said, "It's a pleasure to put a face to the name. I didn't expect you to be so young!"

"Please, call me Stephanie," I'd say, crossing and uncrossing my legs, sliding the contracts across the glass.

"Well, Stephanie, can we go through the numbers one more time? Because there seem to be a few items here that maybe none of us anticipated."

"By all means. I don't want there to be any surprises." Lao Ting taught me how to speak this way.

I would walk them slowly through the revisions, refuting their objections before they could even raise them. "Keep them nodding," Lao Ting taught me. I worked the older ones against the younger ones.

"You see, I told you that was the issue," one would say to the other while I smiled.

"Don't predict your needs based on past performances or, for that matter, the Chinese expectations," I liked to add. "Our services don't work that way, which is what makes us so attractive. Most companies that coordinate American and Chinese contracts can't navigate those waters. Still, if you'd like to speak directly with the Chinese . . ."

"No, no. Of course, of course. We understand," the businessmen would say, and I'd stand and lean across the desk to point at where Gigi had stuck all her colored arrows.

If their pens still wavered, Robbie got nervous in the silence. He said, "Everything is underwritten, of course. We have bonded insurance, blah-blah. But please, don't sue us!" "Let them think," I said. "Let the men think." The businessmen signed everything I gave them. They were always eager to please me, eager to show that they were on my side. Nobody ever sued Lao Ting.

Robbie was a handsome homosexual from Arroyo Grande and very talented, I thought. He was a health nut. Every morning he jogged twelve miles barefoot on the beach. He took frequent trips to Hawaii to meet with a medicine healer to repair his spirit. In a past life, Robbie was a mule and horribly brutalized by his master. Robbie said he was starved to death in a stall the size of a small closet.

"What country were you a mule in?" I asked him once.

"Russia," he said. "About twenty miles from Finland. The summers were the worst because the sun was up all day and night, and my master had insomnia. He suffered from psychosis and nobody understood him. He'd ride me out into the forest where nobody could hear him, and then he'd beat me, screaming and crying. God, it was awful. I felt for him, too. It's not that I didn't feel for him. I just can't get over how he put me in that stall. He was too cowardly to cut my head off, I guess."

"Did he abuse you sexually?" I asked.

''Just emotionally," Robbie said. "My healer is having me take this ancient lava ash. It makes my tongue gray, so I have to suck on red candy." He stuck his tongue out to show me how red it was. "For when I have auditions."

"Looks good," I said.

"All natural ingredients. But it still rots your teeth. Any sugar will do that. Even fruit. But I'm feeling a little more grounded now, I think, taking the lava ash."

Robbie didn't eat meals with the family. He lived mostly on vegetable juices, nuts, and herbs. The family didn't judge him for that. They supported him unconditionally. For his birthday, they gave him a little almond tree. For my birthday, they gave me a white silk robe with a pink dragon embroidered on the back. Lao Ting and Gigi were the kindest people on Earth. They were the most tender souls one could ever hope to find.

"You're going to get over what happened to you, I'm certain of it," Gigi said to Robbie. "I had a dream last night you were a white stallion, running free across the tundra."

"Yes, you will come out a winner. And dear, dear Stephanie Reilly," Lao Ting said across the table. "You and Robbie are doing such a good job. We feel happy to have you two in our lives. Our beautiful American son and daughter. We are so proud of you. Look at you both! So handsome! So pretty!"

Lao Ting had a digestive issue that restricted his diet to shrimp and boiled yams. The digestive issue seemed to be well managed by this diet, and by his daily regimen of swimming and stretching and Ping-Pong. Because he was the patriarch of the family and the boss of the business, and because the family was disciplined in their loyalties, shrimp, yams, and rice were all that was offered at meals. I once asked Lao Ting whether he ever grew tired of eating the same foods again and again each day.

"I never grow tired of food," he answered and slapped at his narrow torso.

I wasn't keen on cooking for myself. I had fancy flatware and some cast-iron pots at home, but I preferred taking party drugs to making food and eating it. During the workweek, all that I ate I ate with the family. I liked the rice they made. It was cooked in an enormous bamboo steamer and tasted of old wood, like the way an antique store smells. The shrimp were boiled whole, then slathered in butter and Chinese spices. The family ate the shrimp by first biting off the heads. They'd spit the little antennae and black spidery eyes out on the ground between their plastic footstools, which they used as chairs around a low table in the dining room. Then they'd put the whole shrimp in their mouths, chew them up, and spit out the exoskeletons. The eldest son Jesse, swept and mopped the dining room after every meal. There were four children—three boys and one girl. All but Jesse were still in high school. When they came home, they helped their parents with paperwork and tidied up. The complex was always very clean and smelled of burning incense. All the floors were flesh-colored marble. The walls were decorated with big crosses woven out of red silk ropes. "These are from China," Gigi told me. "They're good luck. They signify birth and prosperity."

Once Gigi showed me on a map where the family's ancestors were from. "My mother's mother's father is from this city. Lao Ting's mother's father's mother was born here, on this river. My father's mother's mother is from this village. You see that dot? It's so beautiful there. You know mist? There's so much mist in that place. It's like a big ghost, the whole village is one big, happy ghost."

"I would like to go there sometime," I said.

"You can go anytime. There are all kinds of magic stuff there. Maybe you can go there and go crazy. You need to go a little crazy sometimes, have a little fun. Sometimes I think you look sad too often. But I think you're going to be happy soon. Here, let me say a blessing."

I never told Gigi about my pituitary situation, which was the source of all my sadness. Anytime I had a cold or a rash or an upset stomach, Gigi would make a tincture from Chinese herbs she kept in a locked wooden chest in the master bedroom on the second floor. Each tincture had a different flavor, and it usually made me well again. I am sure that if I'd told Gigi about my situation, she would have made me a special tincture for that, too. And then every day after, she'd be asking, "Is it better? Is the flesh smaller now, or still so swollen? Poor Stephanie Reilly. You are so pretty. We need to get your gah-gah healthy again."

One night I had a dream that Gigi told me to make a radio program out of the demon voices inside of me. I did so, and when I put the program on the air, the world heard the evil things the demons were saying, and everybody went crazy and killed themselves. In bed, as I dreamed, I became paralyzed. The ceiling opened up and an alien spaceship lasered down a powerful ray of vacuous light and exorcised all the demons out through my chest. It took about ten seconds.

"I wonder if they're really gone," I told Gigi. "If they are, I wonder what I'll do. I wonder if I'll be different from now on."

"I had a dream last night, too," Gigi said. "I met a young woman in a little shop somewhere. It was just a small momand-pop, dirty, not very nice. This young woman took a drink from the shelf and broke the bottle on the floor. Then she started eating the little shards of broken glass. I tried to pull her off the floor. 'Don't do that, sweet child!' I was yelling, but she used the shards to cut my arms. Her hair became tangled in her face. She had hair like an African American woman when they get it ironed. It was like ribbons tied in knots across her face. When I woke up from this dream, I was thinking people could try wearing their hair like that, tied in knots across their faces. If it were done well, it could be very decorative and beautiful." She turned to her daughter, who had long, straight black hair. "Maybe you'll let me try some designs on you later." The girl chewed her food and waved her chopsticks back and forth. "No?" said Gigi. "You'll be sorry." She laughed. "I hope your demons are gone, sweet Stephanie Reilly. But please don't change too much. I'd miss you. We would all miss your warm, fragile spirit."

*

The demons didn't leave me, though. They were always there, taunting me, filling my pituitary with poison. One day, after a successful business meeting, I told Robbie about my pituitary situation as we drove back to the complex.

"I can understand your frustration," he said. "My healer says that the body erupts from the mind. Everything is emotional. Ideas and feelings. Is there some emotion you are storing up in your pituitary, some negative feeling that makes your genitals so big and gross?"

"I guess I have a lot of emotion stored up. But it's nothing bad. It's love. It's just love rotting up inside of me."

"I've never heard of such a problem."

"That's it," I said. "I have too much love, I think, and nobody to give it to."

"What a conundrum," Robbie said. "I can give you the number of a magician I know. He converts energies so they can be purged and donated to people in need."

"It would be nice," I said, "to help somebody out."

"When I had tendonitis, he transferred the inflammation onto a dying mosquito, he told me. And then later that day a mosquito bit me. It was wonderful. I don't know if it was the same mosquito, but my wrist felt better almost instantly."

"That's amazing, Robbie," I said.

"Life is amazing, Stephanie Reilly. We won the jackpot, getting to live on this beautiful Earth. When I can keep that kind of positive attitude, a madman can beat me all he wants. He can break every bone in my body. There is no pain," said Robbie. "Experiences are just time passing in different ways. Time passes and continues on and on. It has nowhere else to go. Call him." He wrote down the magician's phone number on the back of a business card.

"You know what happens when you jump off a bridge?" This was another man I remember. He had a scar across his forehead like a third eye. I found him panhandling outside the liquor store in Saticoy. He was intense and perturbed and smelled like motor oil and vomit, which is what drew me to him. I told him he could sleep on my couch if he promised not to touch me, and I took him home to the loft. He was just a kid, it turned out, only nineteen years old. He'd run away from his home in Nebraska and was thumbing rides down to Venice Beach. "Basically you bleed to death," he told me. "Your bones turn into knives inside your body when you hit the water. Or your heart explodes under the pressure. And you break your neck. Can I use your bathroom?"

"Sit down," I said, pointing at the couch.

In the cab, he'd talked like this: "You know how many murdered bodies never get discovered? You know how to tell if a person's soul has left its body? You know that guy back there outside the liquor store? I think he's possessed or something."

"I'm possessed," I told him. "Many people often are."

"What's it like? Do you speak in tongues? Do you ever do things you regret but can't take back?"

"It's not like that," I said. "It's more of a medical issue." "Do you know that there are people in India, if you cut off their hands, they'll just grow back new ones? Some people have special powers. I wish I could go to India. I like your apartment. Is your husband home? Is he down for whatever?" I did not strip for the boy. I gave him what little I had in my fridge to eat: an apple, yogurt, chocolate-covered almonds, a frozen samosa. We sat together on the couch, discussing all the different ways to die. By sunup, I had my pants down, asking for his opinion on the situation, hoping he'd say he'd seen so much worse. But he had not.

"You should come to India with me," he said. "Gurus, special doctors, chanting."

"There's always surgery," I began to say.

"Yeah, but that won't get to the root of the problem. The demons, right? You're still really pretty, though," he said. "You have that going for you."

Life can be strange sometimes, and knowing it can be doesn't seem to make it any less so. I know I don't have any real wisdom. I don't have any wonderful ideas. I am lucky to have found a few nice people here and there.

Lao Ting went swimming in the ocean one morning and never came back. They sent boats out there to try to find him, but he was gone. He was probably eaten up by sharks, the family said. There was no funeral or missingperson report. But there was a memorial service, just a family meeting in silence on the patio at sunset. I came for the last few hours. Robbie was away, filming an exercise video with his medicine man in Hawaii. When the sun went down, Gigi gave everyone a cup of special tea, and when I drank it, I fell asleep on the white leather love seat and dreamed of nothing, not a sound, just whirling gray air in an infinite space. In the morning, the children packed up all of Lao Ting's belongings. A Goodwill truck came to collect the boxes. It broke my heart to see how tidy everything was, how neatly Lao Ting could be put away.

There were no more meetings, no more businessmen, no shrimp, no yams, no rice. Gigi ordered fried chicken and let it sit out in the dining room, orange oil seeping through the paper buckets and staining the white tablecloth. But she was strong. I never saw her shed a tear. The sons went down to the beach and lit paper documents on fire and stared out into the water and screamed out their sorrow. The daughter stayed in her room, listening to twinkling music on her computer. Without Lao Ting, the company could not function.

"It is the best thing," Gigi said, signing my last paycheck. "We will sell the complex: We don't need all this luxury. You know, Stephanie Reilly, when I met my husband, I was a teenage prostitute. I did things I hope my daughter never does, not for money, nor for free. When Lao Ting first saw me on the street, I was just a skinny Chinese tramp in a bikini top—can you imagine? All my dreams were nightmares back then. Nothing good. Nowhere safe to sleep. Lao Ting gave me this." She unbuttoned the top of her black mourning gown and pulled out a tiny bloodred stone hanging from a gold chain around her neck. "He told me this stone would mend my broken heart. Fancy words, romance—I know how silly it sounds. But it worked. It made me strong. That is not the whole story. Just to say, Stephanie Reilly, we all need to have composure. We need some solid stuff to hold on to. When I look at you, I see fine loose threads, like a silk cushion that has been nibbed for a hundred years, poor girl."

A few years later, when I was desperate and wanted to end my life, I called Robbie's magician. By then I was living in a rented room in Van Nuys, taking the bus down to Tijuana every month to buy special hormones a doctor had said might balance the situation out a bit. It wasn't working. On the phone with the magician, I explained my situation. I cried.

I said, "On a good day, every small thing is enchanting. Everything is a miracle. There is no emptiness. There is no need for forgiveness or escape or medicine. I hear only the wind in the trees, and my devils hatching their sacral plans, fusing all the shattered pieces together into a blanket of ice. I have found that it's under that ice that I can feel I am just another normal person. In the dark and cold, I am at 'peace.'"

"What is your name?" the magician asked.

So I moved here to Vacaville to be with him. It is good to have someone to turn to late at night, when the voices in my head are loud and there are no drugs to dull them. The magician doesn't mind my swelling. He blossoms like a tree in front of my eyes, a man of seventy-five years, revitalized by my pain and sadness. It makes me feel good to see him thrive.

© Ottessa Moshfegh

This electronic version of “The Surrogate” appears in The Barcelona Review with kind permission of The Random House Group Ltd. ©2017. It appears in the author's collection Homesick for Another World, published by Jonathan Cape, 2017. Book ordering available through amazon.com and amazon.co.uk

This story may not be archived, reproduced or distributed further without the author's express permission.

Please see our conditions of use.

The Barcelona Review is a registered non-profit organization

Author Bio

Ottessa Moshfegh is a fiction writer from Boston. She was awarded the Plimpton Prize for her stories in the Paris Review and granted a creative writing fellowship from the National Endowment for the Arts. Her first book, the novella McGlue, was published by Fence Books in 2014. Her novel Eileen, published by Penguin Books, was awarded the 2016 Pen/Hemingway Award and was shortlisted for the Man Booker Prize. Her short-story collection Homesick For Another World was also published by Penguin Books. It was a New York Times Book Review Notable Book of 2017.

Ottessa Moshfegh is a fiction writer from Boston. She was awarded the Plimpton Prize for her stories in the Paris Review and granted a creative writing fellowship from the National Endowment for the Arts. Her first book, the novella McGlue, was published by Fence Books in 2014. Her novel Eileen, published by Penguin Books, was awarded the 2016 Pen/Hemingway Award and was shortlisted for the Man Booker Prize. Her short-story collection Homesick For Another World was also published by Penguin Books. It was a New York Times Book Review Notable Book of 2017.