MICHAEL BUNN

MICHAEL BUNN

ALL WE GOT

Desperation is rarely a useful currency in any venture, whether it be romance or business, but a dismal weekend spent fretting over those two particular areas of my life has driven me to a precarious state of mind. And so, as I stumble along one of Barcelona’s grimier streets on this overcast Monday morning, I prepare to make two rather desperate phone calls.

Stopping on a corner I take a deep breath, tap on my mobile phone, raise it to my ear and close my eyes as if in silent prayer.

My first call is to Javier who, being a publisher, doesn’t sound too pleased at being raised at 8:45 on a Monday morning. I tell him what I’ve heard from another translator, that Javier’s publishing house has just been entrusted with the translation, into English, of a prize-winning novel by a writer from the north of Spain whose work I absolutely adore. I make my pitch, trying to sound confident and not stutter, then I listen as he rambles on, in that pompous way of his, about the importance of the project, the agent’s demands and so on. At last he gives me an answer to my question, but it’s not the one I’d been hoping for.

Over the past two years I’ve translated several novels for Javier, all of which he’s been happy with, and I was hoping he’d give me first crack at this one, but no. It turns out that before I can even get a sniff of the action, two other translators will either have to come down with long Covid, be jailed for tax fraud or just drop dead. There’s nothing more for me to say, so Javier ends the call with a vague rhetorical flourish which, like most of what emerges from his mouth, means very little. I open my eyes to find that I am standing on Carrer de la Lluna, in the heart of Barcelona’s old city.

I left my flat in the uptown part of the city some 40 minutes ago, hoping that a brisk walk would burn off some of the nervous energy that had been building up in me over the weekend, so I would be in something approaching a fit state to make the two phone calls I had to make. Wandering aimlessly, I walked down Aribau, crossed the Gran Via, which was already honking and grumbling with morning traffic, until I finally ended up in El Raval, that old part of the city which continues to resist gentrification.

The street reeks of human effluent resulting from years of Airbnb tourists pissing litres of lager and cheap cocktails up the walls, and I move on quickly to avoid being sprayed by council workers hosing down the street to wash away the muck and stench left by the past week’s holidaymakers. Along the street, shutters are sliding up with shrieks and rumbles, as if each shop were opening a bleary eye to greet the new day. A dead rat lies in the gutter, eyes bulging and mouth agape as if taken aback by the way things have turned out. Even a rodent can’t catch a break here.

I stop at a corner, take another deep breath and make my second call of the morning. She’s an early riser, and so her tone of voice – which today ranges from the offhand to the slightly irritable – can’t be put down to disturbed sleep. But we’re speaking, at least, which is a straw worth clutching at. I haven’t phoned her for a week now, in the hope that she might actually ring me, but it doesn’t sound as if my absence from her life during those seven days has been too hard for her to bear. Even so, love-blindness means never taking ‘no’ for an answer, and so I do my best to turn our initial hesitant exchange of syllables into something more promising.

I tell her about Javier and the book that I might get the chance of translating, and she responds with an indifferent grunt. I try to elicit a little sympathy by telling her that translation work has been thin on the ground recently, thanks to much of it being swallowed up by the digital pestilence that is ChatGPT.

“Well, good luck, anyway”, she says. In my wretched state, I try to glean some kind of encouragement from her words, but I can’t get past that “anyway”.

“Maybe we can meet up later, then”, I suggest, a little over-enthusiastically, “to celebrate, or something?” I clap my free hand over my eyes and grimace. Celebrate? Who am I kidding? Celebrate the off-chance of me getting a little gainful employment? But there is no dignified way to take back the remark.

“Yeah, maybe”, she sounds distracted. Good, with any luck she didn’t hear it. But before I can make amends with some kind of droll wisecrack, she says, “All right then, give me a call”. And with that she’s gone.

The sun has burnt its way through the morning fug of car exhaust and general airborne filth and I blink in the glare as I carry on down the street, mulling over my two dispiriting phone calls. Then I glance to my left and spot something that stops me in my tracks.

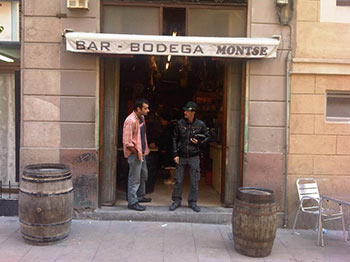

Bar Montse reads the sign over the door, beside which hangs a battered blackboard promising Comidas y tapas. I’m amazed: I can’t believe this place is still open. From the outside, the bar doesn’t seem to have changed since I first came here twenty years ago, though the windows are too grimy and smeary for me to get any idea of what’s inside. On an impulse, perhaps to distract myself from the realisation that both love and money have forsaken me, I push the door open and walk in.

The door creaks shut behind me and I pause for a couple of seconds to allow my eyes to grow accustomed to the gloom. The bar has clearly resisted the modernisation that swept through the city after the 1992 Olympics: the walls and ceiling still wear that nicotine patina dotted with fly shit that takes decades to perfect, while the local fiesta posters, photos of forgotten celebrities and yellowing newspaper cuttings that festoon the walls are all curling with age. The residual fragrance of stale coffee, greasy fry-ups and unreliable plumbing completes the effect.

“¿Qué quieres?” comes a shrill voice from the other side of the room, and I am delighted to see that Montse is still on the planet. Ancient, stick-thin and wrapped in a kitchen apron that bears the stains and splashes of a thousand platos combinados, Montse has evidently not undergone any kind of customer service training since my last visit; her sharp face peering out over the cash register wears the same unwelcoming scowl that I remember from decades ago. Perhaps she’s wondering whether I’m one of those hipsters about to brandish a shiny digital appliance and ask for the bar’s Wi-Fi password. Fat chance of that – by the looks of it, Bar Montse has only recently upgraded from candles to electric light.

“Café con leche”, I reply, and she turns to begin cranking up a coffee machine that looks ready for decommissioning to an industrial museum. I nod a greeting to a couple of elderly men engrossed in a game of dominos and I’m just looking for a clean table to sit at when I hear a gravelly voice bark “Goddamn it!”

I turn to see a man in the corner, bending from his chair to pick up sheets of paper that are scattered across the floor. I step forward and pick up a couple of sheets that have floated out of the man’s reach and hand them to him. I notice that they are covered in spidery handwriting.

“Thanks, man”, he says, as he sorts through his papers. The voice is gruff and raspy, the accent American. My initial reaction, when he looks up at me and I get a glimpse of his face and clothes, is one of mild pity. What a pathetic creature, I think, travelling all this way, across the Atlantic, to spend his time in a European city posing as the singer-songwriter – one of my long time heroes – who amalgamated cool jazz and the spirit of the Beat Generation into popular music. But just then, as he begins awkwardly stuffing the sheets, sheaf by sheaf, into a leather shoulder bag, he grumbles,

“Well if this ain’t a mess, it’ll do until the mess comes along”, and something flips in my head and my jaw drops.

It’s him. It’s not some wacko impersonator, it’s definitely him. There’s no way anyone could pull off such a perfect imitation – just look at those beady little eyes behind tiny half-moon glasses, that reddish mop of hair turning grey beneath the battered trilby, the jutting jaw, the awkward theatricality of his movements, but most of all that voice: that sandpaper baritone, as the New York Times called it, which has made him famous all round the world.

I spot another sheet of paper under a chair, pick it up and hand it over, wondering what to do or say next. It’s not easy to operate normally when your everyday life is suddenly irradiated by the glow of celebrity. He nods as I hand the sheet of paper to him, and I say, “You’re welcome”.

He looks up at me, raises his eyebrows and nods: a Brit. Then he says, in those deep, rumbling tones that I know so well, “I was just thinking, maybe I could ask you whether you knew any place round here where a person could get a decent cup of coffee. But then again, since you’re here”, he gives the mug of black coffee on his table a look of disgust, “I guess you don’t”.

“Well, yeah”, I reply, “This place is pretty shitty. I only come for the memories”.

“The memories”, he repeats with a throaty chuckle, as he gazes round this crumbling mausoleum of bygone catering and merrymaking. “So where’d they keep the good ones?”

As if on cue, the sour-faced Montse hobbles towards us, bearing my coffee in her shaky hands. I drop a five-euro note on his table to pay for both of us, and say to him, “I know a place”.

*

This has to be the most surreal experience of my life – walking through one of Barcelona’s seediest districts with the man who has spent most of his music career writing paeans to the deadbeats and no-hopers who scratch out a living in this kind of underworld.

“In here”, I say, and we enter a coffee bar that’s only just round the corner from Bar Montse, but it’s light years away in every other sense. Stylish in its Zen simplicity, with pinewood tables and artsy black-and-white photos on the walls, it’s hipster heaven, and this is confirmed by the presence of five young people, silent and solitary, sitting at separate tables, transfixed by their laptops.

We order at the bar and once again he chooses a corner table, away from the window. There is a brief silence as he looks around, scrutinising the photos on the walls, which are mostly generic art school fodder.

“So”, I say, “You just passing through?” And I send up a silent vow to make that the very last cliché of our conversation. Fortunately the waitress intervenes, bringing us our coffees. She’s in her early twenties, pretty, with short fair hair in a pixie cut, like Mia Farrow in the ‘60s. He follows her with his eyes back to the counter, a melancholy expression on his face, perhaps rueing the fact that she’s much too young to recognise him, and he’s far too old to interest her. He sighs and turns back to me.

“Well, I woke up in some fancy hotel over that way”, he gestures vaguely, “And I just made up my mind to get out and do me some exploring”. He pats his leather bag. “And take a look through some notes. You?”

“Me?” I reply, flustered, “Oh, I live here. Have done for years”.

He grunts and takes a slurp of coffee, then gives an appreciative nod.

“Good coffee”, he says, and once again I’m struck by the surreal nature of the situation: it’s like a weird re-enactment of Coffee and Cigarettes – that series of shorts by Jim Jarmusch he appeared in.

I’m casting around in my mind for some kind of compelling conversational gambit when he says, with another deep sigh, “Far from home”.

Is he talking to me? I wonder whether I’m expected to reply when he goes on, “Trouble is, you spend a long time away, and when you go back you realise you’re still far from home, and you’re always gonna be”.

“You’ve changed”, I say, hoping to elaborate on the theme, “And you’re stuck there”.

“Neither here nor there”, he nods in agreement and sips more coffee. He seems very sad.

“I just got in from Madrid”, he says, finally making eye contact. His eyes are small and bright blue, and the way they dart around furtively gives me the sense that he’s extremely shy.

“Working?” I say. I’m not going to let on that I know who he is; it would break the spell of what is without doubt one of the most magical experiences of my life. If I did let him know, ask for an autograph or something, then I’d become just another adoring fan instead of what I am at the moment: an ordinary guy shooting the breeze with another guy over coffee.

“Doin’ some work, yeah”, he says, “Researching a project. About Lorca”, and he taps the side of his nose with his forefinger. I nod, trying to rein in my amazement. Am I in on a secret now?

“Ever been to the Prado?” He pronounces it ‘Pray-dough’, and I wonder if he’s playing up the dumb Yank act. I nod, yes.

“Some great stuff in there, no doubt”, he says, his fingers thrumming on the table as he speaks: it looks like the fidgeting of an ex-smoker. “But…” his gaze drifts back to the waitress, who’s standing behind the bar, looking at her phone and smiling at something.

“But there’s so much death in there”, he says, with an agonised grimace. “So much. And it’s everywhere”, he adds, picking up a newspaper someone’s left on the seat beside him. The front page shows a scene of terrible carnage: blood-spattered children wailing in terror.

“I mean, is that all we got, for Chrissakes?” He drops the newspaper and holds up his hands as if in supplication. I have nothing to offer, and he shakes his head, then lifts his empty cup to the waitress, who smiles and turns to her coffee machine.

“So much”, he says, and rubs his face with both hands.

His outburst casts a pall over the conversation, and I remain silent as he takes off his trilby and scratches his head. His hands are in constant motion. He replaces his hat just as the waitress brings him a fresh cup. Then there’s a bit of vaudeville as he raises his hat to her and gives her his best salesman’s grin. She laughs and walks back to the bar.

“Maybe try Pascal’s wager”, I suggest, and he frowns and shakes his head. I can’t believe he’s never heard of it.

“17th century philosopher, had the same problem”, I tell him. “Decides to make a deal with God”.

“Running up that hill”, he sings softly, deadpan. I ignore him and carry on.

“Declares that he believes in God and heaven because if they do exist, then after he dies, he’s sorted. And if they don’t…”

“Then it doesn’t matter a damn”, he says with a grin, and claps his hands, once. “A cure for death. Neat!”

My phone chirps in my pocket and I take it out. A message from Javier.

Sorry, Tony Baker’s agreed to translate the book.

“Got a message?” he asks.

“It’s nobody,” I say, and he lets out a rasping chuckle.

“That’s the trouble”, he wags a finger at me, “When someone calls, it’s usually nobody.”

I laugh too, and relax, allowing the pleasure of his company to neutralise the bad news. Here he is, just being himself, for my own personal entertainment. I decide to reciprocate confession-wise, and tell him that I’m a translator and I just lost the chance to translate a major novel.

“Well, now”, he says, with a frown. He fishes around in his shoulder bag and takes something out. It’s his mobile phone, an ancient, battered one. It’s a smart phone, but only just. He taps in the password and it begins peeping and trilling. He scrolls through his messages, tutting in irritation.

“Damn thing”, he says, “I keep it turned off most of the time. These messages eat away at your soul. What’s your name, by the way?”

“Jerry. Jerry Nolan”.

After a good deal of tapping, huffing and puffing, he finds what he’s looking for and, taking out a notepad, starts writing on it. As he writes, he mutters to himself: “Jerry Nolan. I knew a boxer name of Jerry Nolan. Back in San Diego. 1974. Or ‘75”.

At last he rips out the page and hands it to me.

“There you go, champ”.

The message, written in the same spidery scrawl that I saw on the sheets of paper, reads:

Hola José Antonio, I can heartily recommend Jerry Nolan, he’s an okay guy looking for translation work. Smart dude, can tell you all about death. Yours as ever, Tom.

Below the message is a name – José Antonio Torres – and the address of a department of a big publishing company in Madrid.

“Stick that in an envelope along with your resume and post it to him, see how it goes”, he says. I thank him and he holds up a hand, no problem, and gets to his feet.

“Got to get back to the office. Been AWOL for too long. The bean counters get antsy”.

We leave the coffee bar and walk straight into a commotion on the street. A girl on an electric scooter has collided with a boy cyclist at the crossroads, leaving both of them sprawling on the cobbles and yelling at each other. A crowd gathers, each person loudly voicing their opinion as to who had right of way. But then, as quickly as it started, the dispute is over, and the injured parties ride off in opposite directions. I watch him smiling, enjoying the scene; the way the mêlée spontaneously ignites, then dissolves into nothing. The energies of life played out before our very eyes. As the crowd disperses, the sound of someone mistreating an out-of-tune piano comes jangling down from an open window above us.

“The piano has been drinking”, I say, and he frowns and tilts his head to one side as if disappointed in me.

“Asshole”, he says, claps me on the shoulder and turns to walk away. Then stops and turns back.

“Good to meet you, Jerry Nolan. Watch out for those memories”. And with that he sets his trilby on his head, the peak angled downwards over his eyes, and moves off down the street with that same slinking, shambling gait that I recall from when he emerged onstage at Hammersmith Apollo, bellowing through a loud-hailer like a fairground barker.

After he’s faded into the distance I make another call. I tell her about what’s happened since we spoke earlier, and she’s absolutely thrilled, as I knew she would be. “Downtown Train” has always been one of her favourites.

“Yeah, let’s meet up tonight!” she says, “I want to hear everything. Did you get a selfie with him?”

“A selfie? I say in disbelief, “With him? Puh-lease! You think he’s a selfie kind of guy?”

“No, I guess not”, she says, “Okay, see you tonight. Bye!”

As I walk back up towards the Gran Via and the golden light of his charisma begins to fade, I try and get things straight in my head. I’ll write to José Antonio in Madrid, of course, and hopefully he’ll give me some work. Having said that, this might be something Tom does for people all the time, and José Antonio might not even bother to reply. Oh well, nothing ventured...

As for her, yeah, she’s radically changed her tune, so impressed is she that I’ve met one of her heroes. But is that any basis for a relationship? Face it Jerry, I say to myself: as the title of the movie goes, she’s just not that into you.

If there’s anything positive I can take from the events of the past couple of hours, it’s that beyond the chimeras of love and money, I have discovered, once again, that the world is a place where magic can happen at any time. As it did to me this morning, when he of all people seemed to manifest into existence out of the mouldering walls of Bar Montse. But we can’t just sit around waiting for the magic to come along, there has to be something else.

Is that all we got?

His tragic expression as he asked the question is etched on my memory, and I still have no answer.

I arrive home and, feeling restless, decide to clean out my office. Maybe a little feng shui will attract some of that good stuff I need right now. But after a while, sitting on the floor sorting sheets of paper into piles, I stop and gaze out of the window, watching a tree’s branches swaying in the breeze. I remember a friend I haven’t spoken to for a while, and reach for my phone. I’m going to give him a call, just to say hi.

© Michael Bunn 2024

This story may not be archived, reproduced or distributed further without the author's express permission.

Please see our conditions of use.

Author Bio

Michael Bunn is an author, journalist and long-term Barcelona resident. His first novel, Jumping at Shadows, a tragicomic tale of three people travelling to the other side of the planet in an attempt to outrun the consequences of their respective pasts, is due out in 2025.

Michael Bunn is an author, journalist and long-term Barcelona resident. His first novel, Jumping at Shadows, a tragicomic tale of three people travelling to the other side of the planet in an attempt to outrun the consequences of their respective pasts, is due out in 2025.

The Barcelona Review is a registered non-profit organization