HEATHER FOWLER

HEATHER FOWLER

You Remember, Jeanie Bean?

You remember the time that guy tried to push mom up against the wall when he wanted to mug her, except we were trailing behind, and then he saw us, and I got nicked in the side with his switchblade as we stood in front of the Rite Aid on Santa Monica Boulevard, with you standing as tall as my hip? I shoved you behind me. You didn’t see nothing. But you screamed. A bunch of people came out. And the guy ran off.

You remember the other time when we were home and I found that bullet that had flown through your window but got rid of it before anyone else could see it because it hadn’t hit anything, except you picked it out of your trash and asked me about it—and I made up some story about how I found it on the way home but then thought it might be dangerous so I had thrown it away, but you pulled it back out again and wanted to tell the neighbors about how great it was I found it and I shoved you against the wall with my fists on your shoulders, grabbing your green and gray shirt, and made you promise you would not tell—I did kind of threaten to kill you then, if you told, but you never told and I wouldn’t have killed you anyway, Jean—remember that?

We know what the other will do. This is why we’re such good brothers. It's like how you let me call you this nickname I've used for years, though we both know your name should sound like John, not Gene. Though mom hates it. Or maybe I do this too to push you away. But you push back.

And you remember that day when we both ate ice-cream, chocolate malted crunch and mint and chip because a big fight was brewing over at the neighbors, at grandma’s neighbor’s, mom was working, and the whole neighborhood was involved because it involved all the kids, but not us; we were eating ice-cream and staying the hell out of it. I wanted to be the hell out of it and I glued my eyelashes shut the day before, or maybe I glued yours too. You did pitch a fit. Much of the time.

You remember growing up without me after I left the apartment? How I stayed away for so long and didn’t return your calls? Of course you remember that, because I heard about it in therapy, thanks Jeanie-bean of the endless rage and artist-like regret.

Well, I guess it’s time to 'fess up. You were younger then, and I didn’t tell you the right side of things before because you couldn’t handle it—and it’s not that I’m trying to ruin your childhood now, but it’s really not fair, all that shit you said to me in therapy two months ago, nor is it fair what happened after that, which is why I need to tell you some things now. Don't interrupt. I’ll start at the start, just how you like it, all clean room and orderly.

This explanation is in order of your emotional concerns and will discuss how you believe I have ruined your life. Somebody should hand me some water now. My head throbs. My nose itches. This could go on: In the first place, I needed stitches that day you say I destroyed your emotional fabric (and bookmarked your birth-date as an artist, oh the suffering) as we sat in the car after the Rite-Aid experience, which is why mom dropped you at grandma’s and we then went to the hospital, and you were just a blubbering baby anyway, but that’s why I didn’t let you touch me in the car, because my side was wet with blood, but I was trying to smile, for you Jeanie-bean, I didn’t want you to know how bad I was hurt, and that’s why I said those nasty things to make you cry, so you wouldn’t lean up against me or get near me, because I could see you were verging on that and I didn’t want you to feel the wet of my blood, or see the blood leaking down onto the seat behind me, if possible, though I leaned hard on my side to try and staunch it—nor did I want my blood on your little blue coveralls, especially not as you were about to go to grandma’s—because grandma didn’t need any more worry, Jean-bean, not grandma, and mom was not going to tell her any of this.

You don’t remember how hard, at the pay phone blocks away, mom worked at masking her voice—but I do, because I watched her stab her own hand with a Bic pen from her purse as she tried to smile, but her face was a grimace, and the whole time, "So, mom, will you take Jean for a few hours? I need to get some athletic stabilizers for Jordan," then listening to her mother talk, saying, "Okay, we'll be right over," and while doing this staring at me, mouthing, “Don’t tell Jeanie. Just don’t. He won’t understand.”

We always knew you were an artist. And you were delicate.

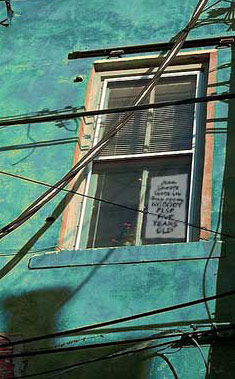

And about the bullet. I had this friend Keith and there were some gangbangers off 37th and Wightman. They were going to kill him and he came running up to the house while you were in the living room watching TV. You never saw him. And then that night you were at Dad’s house because of the split-custody and all, and the gangbangers came and took a shot. Your window, two floors up, faced the alley. They must have seen me walk by, or thought it was Keith, but Keith didn’t live there. And that’s why the next day I explained to you that I made a sign for you to put in your window, so that everyone would know that that was your room. Remember how I told you, “Jeanie-bean, we all need to claim some spaces in our lives and this is your room and I made a sign so that everyone will know it because at Dad’s house you have to share a room with your stepbrother, but not here." And you loved the sign. You said, “Jordan, thank you. I love my sign.” And I said, “I wrote it big, Jeanie-beanie, because that way when you drive up to the house, when mom drives you up to the house, you can always remember that you have a room here. And you can remember how old you are"-- because the sign said:

Jean Shrotz lives in this room. NOBODY ELSE. FIVE YEARS OLD.

And then you were mad at me later that month because I sold the coin collection grandpa gave us and didn’t tell you what I did with the money. I gave the money to those gangbangers Jeanie, because they said they were going to kill my friend Keith. And then they took my money. And they shot him anyway. But in case you were going to bring that up, too, that’s where our coins went. I wasn’t trying to “Rob your meager inheritance of family heirlooms that weren't total shit” as you stated so poignantly two months ago in therapy, and believe you me, I remember every single thing you said there, even though I didn’t defend myself at all.

And about the day you said I tried to explode your stomach with ice-cream. When you were mad because everyone was milling around grandma’s house and you thought I was trying to keep you from Veronica, your one “True Love” of childhood, who was affected too—I did that, I kept you away, because mom’s friend Joan—Joan’s brother, he touched a lot of kids on that block, Jeanie-Bean. And even though you were always clung tight to grandma’s side, even though you were so little and fearful of everything, I knew if you hung around there too much that day, you would know. You would hear the pain of the families, of the mothers, of the mortified children, of the whole screaming block, and so I had to get you out of there. What had happened to me had already happened and I didn’t have anything to say about it, but I couldn’t let you go back. I knew what was happening there, the horrible confrontations, the tears, the families in uproar, and I had to keep you out. I didn’t know how else to do it, so I kept buying you ice-cream and then kept taunting you that you were a little wussy, a little freak, a little worm of a kid brother if you couldn’t eat two scoops and then three, if you couldn’t do it slow, so slow that your belly would be nice and full and you could fill it without vomiting. And then, when I vomited and you vomited, I said we needed some more ice-cream—for the taste in our mouths—but you and me, that day, we were vomiting for different reasons, though you didn’t know that and you would never have to. And then the guy who did the stuff was nabbed. And then he was released. And then he moved.

Years went by. I don't remember what happened. Then I moved, and you were so mad when I moved, when I left mom's, "Abandoning you in the drudgery that was our life," as you say, and you’re still mad, obviously, but everybody was drunk then, Jeanie, everybody was drinking, and I was drinking too, but you were getting good grades. And mom was making more money. And you were painting and talking Julliard for your piano skills. And you were writing Marxist shit. And you were succeeding!

And I was sitting in a trashed little apartment with some girl, or some series of girls, getting loaded out of my mind, angry at the whole fucking world that I could not get my shit together, that I couldn’t have had the protection you had when you were a kid—and yeah, I thought you were a stupid little softie prick. I hated that what you had escaped was simultaneously what I had endured, so I knew some deep, hard envy in my soulless strung-out self about you. So I stayed away. I didn't want it to bleed through. I did miss you though.

And even when I didn't call you, I kept you with me. I kept asking mom how you were. I didn’t return your letters, it’s true. I wandered aimlessly. I blew you off.

I let you be mad and I didn’t even come home for Christmas most times, but it was because you would be ashamed of me, more than you already were. And even if you thought I'd done all those terrible things to you when we were kids, I didn’t want to see your eyes glaring at me when we were both adults, ashamed of me so bad, staring at my greasy hair and old tore-up clothes, when you would undoubtedly say, “Where’s my brother, Jordan? Do I have a brother?” Because you said shit like that, to torture me. But I always had your back, even when what that meant was to protect you from myself. And you excelled.

And then you got your fancy degree. And then you did what all people with money and success do, discovered or decided you were fucked up anyway. And you went to your fancy counseling appointments. And your therapist then thought it was all too important for us to have a group session, which I didn’t feel like doing, amped out on meth as I was then, as I still am now, and so I said I wouldn’t go. And here’s something else that you don’t know: I said I wouldn’t go, but then mother called. And she said, “You get your shitty ass down there right now. You go there for your brother because I know you love him and it’s about time he knew that too. It has been nice when you sent me money to help with his living expenses. You’re not perfect, but go. And go back to NA for shit’s sake. You can do something with you, too. You’re not a lost cause.”

So I did. And then you told me all that shit, Jeanie Bean, about how destroyed you are, but if you ask me, you seem pretty fine. You can get out those Batakas and beat the shit out of a chair to display your rage, which is all real rage, because all of us have real rage. And these issues you vented, they are very real to you, so I’m not trying to steal your thunder or say you don't have valid concerns.

But why’d you try and be a bad-ass and buy yourself a motorcycle? You couldn’t even ride a Schwinn. And now look at you. Leg all cranked up. Peaceful as a dreamer.

I’m only here telling you all this today because you seem like you are sleeping but you might die, and if there’s one thing I don’t want in my life before you die it’s to have gone to that shitty therapy session with you, letting you beat the hell out of me, still protecting you with my silence, with my angry face, and to know that I never ever told you how much I gave up for you, how much I loved you then and still love you, and it’s just easier to know that I’m saying these things to you when your eyes are glued shut again, brother. When that machine keeps showing your heartbeat. And I keep praying that you’ll wake up. I'm really praying to God, who is a merciless no account sonofabitch, but if he has any power here, I'm praying to him now.

And hey, it's Jordan, Jeanie. I've got my hands on your shoulders now. Hands there. I'm squeezing. Your eyes flutter. Your veins seem to flutter. Wake up. Wake up. Jean?

You wake up and I promise I'll say: "Yes, you had a terrible childhood artist boy, Jeanie Bean. Just like you said in therapy. And a mean older brother who would kill you if you didn't pipe down. Who you won't even let spend the night at your ritzy house—and when you go back to yuppie-ville, I'm sure your therapist will be happy to hear from you." But then I’ll be silent again, glaring at you. Or maybe I'll say, "What's up little wuss, brother? Little pussy. I told you not to get a bike. Shit. You can't even ride a Schwinn"—and you know, as much as I love you, because I do, we will not ever have had this conversation.

© Heather Fowler 2011

This story may not be archived, reproduced or distributed further without the author's express permission. Please see our conditions of use.

The Barcelona Review is a registered non-profit organization

Heather Fowler received her M.A. in English and Creative Writing from Hollins University. She has taught composition, literature, and writing-related courses at UCSD, California State University at Stanislaus, and Modesto Junior College. Her work has been published online and in print in the US, England, Australia, and India, and appeared in such venues as Night Train, storyglossia, Surreal South, JMWW, Prick of the Spindle, Short Story America and others, as well as having been nominated for both the storySouth Million Writers Award and Sundress Publications Best of the Net. Her poetry has been nominated for the Pushcart Prize, was recently featured at MiPOesias, The Nervous Breakdown, poeticdiversity, and The Medulla Review, and has been selected for a joint first place in the 2007 Faringdon Online Poetry Competition.

Heather Fowler received her M.A. in English and Creative Writing from Hollins University. She has taught composition, literature, and writing-related courses at UCSD, California State University at Stanislaus, and Modesto Junior College. Her work has been published online and in print in the US, England, Australia, and India, and appeared in such venues as Night Train, storyglossia, Surreal South, JMWW, Prick of the Spindle, Short Story America and others, as well as having been nominated for both the storySouth Million Writers Award and Sundress Publications Best of the Net. Her poetry has been nominated for the Pushcart Prize, was recently featured at MiPOesias, The Nervous Breakdown, poeticdiversity, and The Medulla Review, and has been selected for a joint first place in the 2007 Faringdon Online Poetry Competition.

Her debut story collection SUSPENDED HEART was released by Aqueous Books in December of 2010. A portion of her author's proceeds will be donated to a local battered women's charity in San Diego, CA.

website: www.heatherfowlerwrites.com

See also, from Issue 24, If King Hammurabi