RYAN O’NEILL

RYAN O’NEILL

ENGLISH AS A FOREIGN LANGUAGE

'ə!'my wife-says, as we make love. 'ə! ə!'

This sound, the most common in the English language, is called the schwa. It's in the last syllable of , 'teacher' and the second syllable of 'understand'. It's also the noise my wife makes when she fakes an orgasm.

After a few moments, Julia groans, 'ə əəəəə.. .' and pushes me away from her, although I haven't yet finished. Then, reaching over, she quickly tugs an 'aʊ' (as in 'mow' and 'toe') from me with her hands. Afterwards we lie slightly apart, facing each other. My body is straight, hers arched. We resemble a child's first attempt at writing the letter b.

'Do you know what day is it tomorrow?' she asks.

'Do you know what day it is tomorrow?' I correct her.

Julia shakes her head and I close my eyes.

*

LANGUAGE FOCUS: LISTENING TRANSCRIPT.

'IN THE CLASSROOM.'

John is teaching an English lesson. Listen carefully and answer the following questions.

1. What is the topic of the lesson?

2. Is Bob married?

3. John has forgotten something important. Can you guess what it is?

John: So, let's open our books at page 138. That's one three eight. 'Love and Marriage.' Now, let's see. Bob?

Bob: Yes?

John: Are you married?

Bob: No. I am a spinster.

John: Ha. Er ... No. A spinster is a woman. A man is a ... ? Anyone?

Patrick: A bachelor.

John: Yes. Excellent .Fantastic. And Ya Mei? Are you married?

YaMei: No.

John: Great. And now Patrick.

Patrick: No. I am footloose and fancy-free! Like my friend Bob.

Bob: Fancy and foot? What is that?

John: I'll explain in a moment, Bob.

Patrick: John? A question, if I may?

John: Of course.

Patrick: I read somewhere that the best place to learn a foreign language is in bed. Is it true?

John: Well ... Ha, ha. Well, I think a library might be as good, as useful.

Patrick: No, I meant that having an English-speaking girlfriend is good way to learn English.

John: Ha, yes. Maybe. But ... You see, I've been married for nine years to a Hungarian and I still can't speak a word of her language!

Patrick: Nine years. Congratulations! When is your anniversary?

John: Um ... Sometime this month. It must be soon, I think. But let’s move on. Ya Mei. Could you read aloud the title of the reading comprehension?

Ya Mei: 'Marriage isn't a word, it's a sentence.'

Patrick: Ha ha! That is very funny.

Bob: I don't understand. What is that?

*

As Bob and the other students leave, I clean the white board, then I take my briefcase and leave the classroom. I walk down the hallway to my office, a small L-shaped room lined with grammar books and dictionaries. Taking a seat behind my desk, I open the top drawer. Beside my pencil case is a neat bundle of Julia's old love letters. Sometimes I use extracts from them in class to illustrate common mistakes. "'I very love you" isn't correct. Why?'

I take out a pen and notebook. For the last two years I have been writing an English textbook, which I hope to publish one day. There are sections on all the major skills: reading, writing, listening and speaking. This evening I'm composing a dialogue that will help students practise the many different pronunciations of the letter a.

It's this particular letter that always reminds me of the first time I met Julia, at a bar in Warsaw. I was studying my Polish phrasebook when I overheard her ordering an absinthe.

Fascinated by her accent, I looked up and saw her for the first time. She seemed to be made of superlatives. She had the most beautiful face, the longest legs, the bluest eyes of any woman I had ever seen. Forgetting my shyness, I asked her where she was from and we began to converse. Occasionally, I would glance down at the topics in the phrasebook to help along my small talk. ('On Holiday' and 'My Hometown' were particularly useful.) At the end of the evening, when I asked if I could see her again, she shook her head. Seeing my disappointment, she laughed.

'I'm from Hungary, remember,' she said. 'In Hungary, nodding head means no, and shaking head means yes.'

Later, after we slept together for the first time, I asked her why she had bothered with me that night, awkward as I was. 'Because you were the only man in that room more interested n my a's than my ass,' she said.

'A,' I write now, and then spend an hour formulating pronunciation exercises. After that, I turn to another topic; one that most textbooks choose to ignore. Under the heading 'Bad Language' I have compiled a list of swear words and calculated their offensiveness with a rating from + to ++++. The first entry is "'Ass" (US English) and "Arse" (British English) ++.' I make a note to later expand and explain 'Kiss my ass,' 'You bet your ass,' and 'To kick someone's arse.' On consideration, I also decide to upgrade 'cock' to +++. Then I notice that it's late. When I call home, Julia says carefully, 'Do you know what day it is?'

'It's Wednesday.'

'It's our wedding anniversary.'

When I try to apologise she calls me a word (rated ++++ on my list) and hangs up.

By the time I get home, Julia has already gone upstairs. She is lying asleep on the bed, naked, as is her habit. On her left breast she has written, in black paint, 'Call', and on the other breast, 'Patrick'.

Years ago, Julia grew tired of how I always missed the messages she took down when I was out. She began to write them on her body, knowing that I would see them when I got home. Sometimes when I came back late I'd wake her with the touch of the paint-brush, correcting the mistakes. And then we would make love.

It's been a long time since my wife has made any mistakes in her writing.

*

LANGUAGE FOCUS: PHONETIC SCRIPT.

The International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA) is a system of symbols based on the Latin alphabet, representing the spoken sounds of language. For example, the first line of Hamlet's famous soliloquy is rendered thus in phonetic script:

/tə bi: ɔ:r nɒt tə bi: ðæt

ɪz ðə 'kwestʃən/

The IPA can be an extremely useful tool for English learners as it can help them pronounce new vocabulary correctly, and can mark the stress on unfamiliar words.

Exercise: Change the following sentences from phonetic script to standard English. The first has been done for you.

1. /'læŋgwɪʤ ɪz ðə sɔ:s əv ,mɪsʌndə'stædɪŋz/

Language is the source of misunderstandings.

2. /wɜ:ds ɑ:r ðə fɪ:zɪʃənz əv ə dɪ'zi:zd maɪnd/

3. /ʤu:lɪʌ ɪz fʌkɪŋ pætrɪk/

*

Patrick is Rwandan. He has a narrow nose, large, round eyes and three short scars like the arms of a capital E on his right cheek. I envy him all this. In comparison I'm quite adjectiveless. His English is excellent, though his preference for the longer forms of tenses— 'I am' instead of 'I'm' and 'It is' instead of , 'It's'—can make him sound overly formal. Whenever I tell him this he chuckles, saying, 'I want to have as few contractions as a peasant giving birth in the fields.'

Patrick was one of my first students. I taught him when he was in Elementary. In our second lesson I asked the class to draw their family tree. Patrick wrote only his own name in the middle of the paper and, thinking he hadn't understood, I explained the instructions again.

'No, I understand,' he said. 'That is me. I am the family tree.'

For the first two years I knew him, this was the only reference he made to the genocide. But when he advanced to Academic, he began to write essays and make presentations on Rwanda. This was the one topic that he would never get full marks for, because he would write and speak only in clichés.

'All of my family and all my friends are gone,' he would say. 'They are as dead as a dodo, as dead as a doornail. But I was slippery as a snake. I hid in a pit latrine for six days. Not enough room to swing a cat and it smelled to high heaven. But on the seventh day I climbed out of there like a monkey. Believe me, I didn't smell of roses, and I was hungry enough to eat a horse.'

Finally, I asked him if he spoke of Rwanda like this because it was too painful to talk about directly. But Patrick only smiled and said, 'You took the words right out of my mouth.'

Although his English is almost perfect, he insists we continue to meet for private lessons. At first we had them at home but Julia objected, and so for an hour every week the two of us walk along the harbour, pausing often, like the fingers of a slow reader across a page. If the conversation lulls, Patrick mutters 'Red lorry, yellow lorry' under his breath, for like all Rwandans, he has trouble distinguishing between r and l. He likes to look at the women we pass; sometimes I have to remind him that staring is rude in Australia.

'There is no word for "stare" in Kinyarwanda,' he says sadly. Then he smiles and claps his hands. 'Anyway, let us revise making plans. Present continuous for the future, yes?'

I nod.

'What are you doing tomorrow?' he asks.

'I'm teaching.'

'Really? When are you teaching?'

'From eight till five. What—'

'Can I ask the questions, please?' he grins. 'It is good revision. As I was saying ... What are you doing after teaching?'

'I'm correcting homework for a couple of hours.'

'Around around the ragged rock, the ragged rascal ran,' Patrick says thoughtfully.

*

LANGUAGE FOCUS: PREDICTIONS USING

'WILL' AND 'GOING TO'.

Exercise: Before reading the rest of the text complete the following:

I. I think Patrick is going to................................................................ .

2. Perhaps John will ......................................................................... .

3. It's likely Julia is going to...............................................................

.

*

At five o'clock, when the last of the students leave, I'm on the way to my office to do some marking. Then I think of Julia. I decide to go home early for the first time in many weeks.

It's a warm evening and I take a shortcut, walking down a long street flanked by garages. Sometimes I like to come here and puzzle out the grammar of the graffiti. There's a white car similar to my own parked on the other side of the road. As I walk past I glance at the registration and see that it is my car. I make out the profile of a man in the passenger window.

'Hey!' I shout as I cross the street. 'What are you fucking doing in my car?'

Startled, the man turns to face me. It's Patrick. His shocked expression is almost comical, as if he were miming the word 'surprise' in class. Looking through the window I can make out

a woman's head resting on his lap.

'Patrick?' I say. 'What are you doing fucking in my car?'

The woman looks up. It's Julia.

*

LANGUAGE FOCUS: VOCABULARY.

Study this vocabulary list of the ninth year of John and Julia's marriage. Look up any unfamiliar words in the dictionary.

chore |

missionary |

grind |

mortgage |

ennui |

utilities |

tunnel |

routine |

peccadilloes |

defenestration |

*

Obviously, at the end of the day, I'm absolutely devastated. I stagger away from the car like a drunk, crying like a baby. Julia is calling my name, but I pretend to be deaf as a post. I'm reeling from the news, and in denial. I never knew my wife could be so two-faced. And Patrick. Maybe it was all a dream, I tell myself. But no, it's as plain as the nose on my face. The night is still young, so I keep walking until I find a bar. I order an ice-cold bottle of beer and gulp it down. Then I have another and another until I'm drunk as a skunk. Standing at a table nearby there is a big man with bulging biceps. On his left arm is tattooed the words 'Australias Own'. I take a pen from my jacket pocket and, quiet as a church mouse, sneak up beside him and add an apostrophe to make 'Australia's'. Quick as a flash, I am lying on the floor, seeing stars. My nose is broken and I'm bleeding like a stuck pig. The man kicks me on the side of the head and I go out like a light.

*

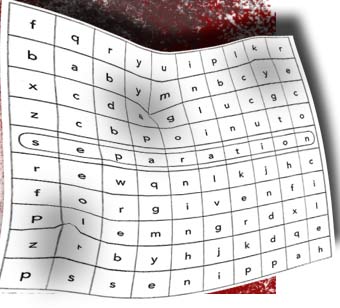

LANGUAGE FOCUS: WORD SEARCH.

Exercise: Test your knowledge of English by finding six words below relating to the future of John and Julia's marriage. The first has been done for you.

*

When I wake up in the hospital, my wife is sitting beside the bed. Julia is no longer made of superlatives, but comparatives. She is less beautiful than before, her eyes are redder, and she seems much older.

With the cast on my leg, and the bandages wrapped round my head, I must resemble a picture from the chapter on 'Health' in my textbook. In fact, Julia's first words to me are exactly the same as in a dialogue I wrote last week, 'In Hospital'.

'What happened?' she says. 'You look terrible.'

I'm about to reply, 'You should see the other guy,' but instead I follow the script and say, 'I had an accident.'

I remember when I first started the school, and I couldn't afford the tapes that went with the textbooks. Julia and I would record the dialogues together. I was the train conductor, the postman, the lost tourist and she was the wife, the receptionist, the chef. We used to laugh so much that it would take us hours to record a few lines. We were happy. But when the students complained that Julia's accent was too difficult to follow, I recorded over her. The dialogues became monologues.

'The doctor said that your ankle is broke,' Julia says and for once, I don't correct her. 'And your nose. Also, three of your ribs, and you have a serious concussion. You could have died.'

'How long have you been seeing him?' I ask, grateful for pronouns so I don't have to say Patrick's name.

'It only started last month,' Julia says. 'He came round one day when you were at the school. There was that time, and the time ... Last night. I have no excuse. It's just that I didn't feel like I was married anymore. Words were more important to you than marriage.'

'Marriage isn't a word,' I whisper, my throat dry. 'It's a sentence.'

Julia raises a glass of water to my mouth, and I drink.

'John,' she says. 'You know ... This was ... I can't .. .' and then, without realising it, she begins to talk in Hungarian. I listen to her, nodding and smiling slightly, as my own students do when they don't understand me. Julia's voice sounds younger. I never realised how beautiful her language is. Soon, she is crying. It's the first time I have seen her cry. Perhaps she couldn't in English. As she goes on, it seems to me that I understand everything she says. Finally, I raise my right hand a couple of inches from the bed. It trembles as if I were a nervous student wanting to ask a question. She stops speaking and looks at me.

Julia,' I say. 'I'm sorry. I'm so sorry.'

She is silent.

'I love you,' I say, and still she says nothing. My hand remains raised. There is one question I have to ask. 'Do you still love me?'

Julia looks at me for a long time. Then she shakes her head.

___________________________

See also The Examination from Issue 80

© Ryan O’Neill

This electronic version of “English as a Foreign Language” appears in The Barcelona Review with kind permission of the publisher and author. It appears in the short-story collection The Weight of a Human Heart by Ryan O’Neill, published in Australia by Black Inc, 2012; published by St. Martin’s Press, 2013.. Book ordering available through amazon.com and amazon.co.uk

This story may not be archived, reproduced or distributed further without the author's express permission.

Please see our conditions of use.

The Barcelona Review is a registered non-profit organization

Ryan O’Neill was born in Glasgow in 1975. He lived in Africa, Europe, and Asia before settling in Newcastle, Australia, with his wife and two daughters. His fiction has appeared in The Best Australian Stories, The Sleepers Almanac, Meanjin, New Australian Stories, Wet Inc, Etchings, and Westerly. His work has won the Hal Porter and Roland Robinson awards. His collection, The Weight of a Human Heart was shortlisted for the 2012 Queensland Literary Prize. He teaches at the University of Newcastle.

Ryan O’Neill was born in Glasgow in 1975. He lived in Africa, Europe, and Asia before settling in Newcastle, Australia, with his wife and two daughters. His fiction has appeared in The Best Australian Stories, The Sleepers Almanac, Meanjin, New Australian Stories, Wet Inc, Etchings, and Westerly. His work has won the Hal Porter and Roland Robinson awards. His collection, The Weight of a Human Heart was shortlisted for the 2012 Queensland Literary Prize. He teaches at the University of Newcastle.