LARRY FONDATION

LARRY FONDATION

JAYSON AND THE LIQUOR STORE

Imperial Highway

Jayson robbed the liquor store at gunpoint. He doesn’t know why he did it. He didn’t then and he doesn’t now. He just did it. At least that’s what he tells people. Even years later.

The gun wasn’t loaded, he says. (If he even had a gun.) But he doesn’t tell anyone anything about the gun. (Like what kind of gun.) Least of all Marta.

The cops never came. So he says.

He said he stole a car, and that the car busted an axle in the potholes before he abandoned it outside the Hawkins’s joint on Imperial, aiming to come back to the projects that, back then, we all called home. They call them “the developments” now—just to make it sound good and fancy—but we still say projects. Concrete blocks stacked upon concrete blocks forming shoebox units, with thick steel doors to resist bullets and intruders, and bars on the windows. Built as temporary housing for returning World War II vets—but sixty-plus years later, still standing. Nickerson Gardens, Jordan Downs, Imperial Courts. Nice-sounding names. But inside the apartments are cramped spaces and the same cinder-block construction on the interior, no drywall. You can’t nail anything to the walls. No wedding pictures, but it’s mostly single mothers. No graduation pix either, but me and my brothers and sisters all dropped out of school. They weren’t teaching us jack. So, we don’t take photos of nothing. But it’d be nice to have the option.

Jayson had a story. And fifty bucks for his efforts, he claimed. The fruits of his labor. The store didn’t carry much in the way of cash. So he says.

I don’t know if Marta was impressed. She didn’t act like it. But she’s never acted impressed in any way whatsoever. Not for nobody. Beautiful, aloof Marta.

We all wanted her. We all talked but never did shit.

That’s what happens most of the time—not doing shit, meaning nothing has happened. I remember one time we asked—“Jayson, what liquor store?”

“The one on Central Avenue.”

Like that narrowed it down.

“What one? R & R?”

That’s at Compton and 104th. It’s so close. And we would’ve heard. Word travels. And why the fuck would you steal a car to skip out on a six-minute walk? It didn’t add up.

“No, you know, the other one.”

Jayson could never prove shit. Of course not. But he just bragged and bragged. He keeps changing his story. Even now. We all know it’s just bullshit. But so what? Like the rest of us, he doesn’t think he has a real story to tell.

A lot of stuff happened. It just all happened before we were born. Or maybe when we were babies—born in 1992, right when something happened. Boiled over; blew up. Then for us, nothing happened. At least nothing much that we think is worth talking about.

I mean bad things still happen of course—murders, robberies, break-ins—we eye our best friend’s girlfriend; we argue, we fight, we want to make something happen. We start shit, we finish shit; sometimes we start shit we cannot finish. But most times we’re bored to shit, and nothing happens, nothing at all, and that’s the worst. That’s when trouble starts. Nobody knows what Jayson did or didn’t do—nobody ever will.

But back in 2009 when we were still kids, Jayson made his first play.

It just didn’t work.

Nobody got Marta. Not even Marta. She made a few commercials, got her face on the side of the bus, shilling cell phones for Cricket Wireless, some such thing. Then nada.

Jayson is in jail now—of course, not for the liquor store heist. The one that probably never happened. But recently, he got himself into tons of bad shit. He’s paying the price.

Right before he got busted, he’d asked me if I wanted to “work with him,” meaning he was offering me the opportunity to deal drugs. He said we could be partners, that he could put some money in my pocket.

“Jayson, I got a job. I make a paycheck; I got a payday.”

“Come on, man. You bag groceries at Food 4 Less. You don’t make shit.”

“I’m good, Jayson.”

“Really, brother?”

“I’m not your brother, Jayson. And I don’t want any part of your fucking bullshit.”

“My bullshit? Man, we came up together. Our mothers stayed at the same place, raised us kids in the fucking projects. Now you think you’re better than me? Why? Because you got yourself some shit-ass job and you moved out? Your whole fucking family is still here!”

“Fuck you, Jayson. You were born full of shit. Like all that ‘I robbed a liquor store’ horseshit back in the day.”

“Horseshit? I got fifty dollars that night. Just by scaring that little motherfucker. He wouldn’t even dare call the cops.”

Jayson is a big guy. No mention this time about any fucking gun.

“Still saying the same old shit. You just made that shit up to impress Marta. And she never gave a fuck about your tired ass no matter what the fuck you said.”

“I’m telling you, dude, I hit that fucking place! And Marta, man, she never gave a fuck about any of us.”

“You got that right. But you know what, I’m out of here. I’m tired of your shit, and I don’t want nothing to do with you or your goddamn schemes.”

For the last time, we went our separate ways. Haven’t seen him since. I think they got him incarcerated out in Chino. But I’m not 100 percent sure. My mother says I should look him up. I tell her I will, but I never do.

So, yeah, I got out. I quit Food 4 Less. I drive a truck now. Delivering for UPS. I’m a member of the Teamsters union. The company pays benefits. I make a decent living.

I moved up by USC. I stay there now. I mostly like it but not always. The people are different. Especially the students. Put it this way: we don’t have much in common.

The 901 is a bar on Figueroa. It’s like the official bar of USC or some such shit. I don’t know why I go there. I mean nobody bothers me. Not physically anyway. Maybe in the back of my mind, I think some rich college chick is going to hit on me, take me home. I look all right. My job keeps me in pretty good shape. LOL, right?

Anyway, one night as I was about to leave—the frat boys’ behavior was bugging the shit out of me—who do I see, flirting with some football-player-looking guy? Marta.

I mean back in the day, Marta looked like a young J. Lo, only better. As I got closer, I could see that she’s still fucking gorgeous; she just looked tired. I was nervous about approaching her. Not about the guy. Fuck him. But it has been a long time, and we were never really close.

The guy moved on. Started flirting with some really young-looking chick. Like high school young. She probably had a fake ID.

When the guy split, Marta looked around; she saw me and rushed at me. What the fuck? Then she hugged me, she fucking hugged me. I hugged her back.

“Oh my God! It’s been forever. How are you?”

We let go of each other. I was even more nervous. I wasn’t even sure she remembered my name. So I offered to buy her a drink. She said yes and we talked and we drank for a long time. I asked what she was up to. She was blunt as hell about what happened to her modeling career.

It was her turn to ask me about my life.

“Do you work around here?”

“No, I stay here, I got a place not far from the new stadium. I drive for UPS. I get to see neighborhoods all over town. It ain’t bad …”

She looked up from her drink and straight at me.

“Are they hiring?”

© Larry Fondation

This online version of “Jayson and the Liquor Store” appears in The Barcelona Review with kind permission of the author. It appears in the collection South Central Noir, edited by Gary Phillips, published by Akashic Books, 2022

This story may not be archived, reproduced or distributed further without the author's express permission.

Please see our conditions of use.

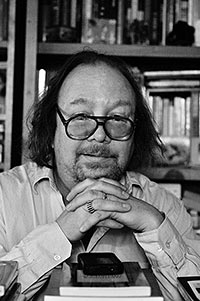

Author Bio

Larry Fondation is the author of seven books of fiction, primarily set in the Los Angeles inner city, where he works as a community organizer. Three of his books are illustrated by London-based artist Kate Ruth. He has received a Christopher Isherwood Fiction Fellowship. In French translation, he was nominated for Le Prix SNCF du Polar. His work in progress is called Single Room Occupancy, set on the fringe of Skid Row.

Larry Fondation is the author of seven books of fiction, primarily set in the Los Angeles inner city, where he works as a community organizer. Three of his books are illustrated by London-based artist Kate Ruth. He has received a Christopher Isherwood Fiction Fellowship. In French translation, he was nominated for Le Prix SNCF du Polar. His work in progress is called Single Room Occupancy, set on the fringe of Skid Row.

The Barcelona Review is a registered non-profit organization