B.J. HOLLARS

B.J. HOLLARS

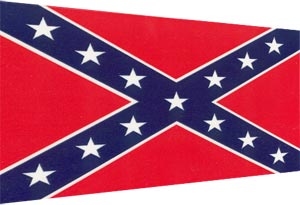

Dixie Land

In his mind, The Confederate lived in a log cabin in the backwaters of Tennessee, beside a rocky canyon and a stream that, many years back, overflowed with the thick blood of Yankees.

Though in actuality, he resided in a 20th century Cape Cod on the outskirts of Nashville. A glowing BP sign illuminated just beyond the neighborhood trees. It was a fine home, complete with a two-car garage, professionally manicured lawn, even a Welcome mat in the backyard that played “Dixie” when stepped upon with the necessary weight.

The Confederate had a son, Confederate Junior, though most called him Junior for short.

While training in the backyard, The Confederate often commanded, “Junior! Bayonet ready?” to which his son snapped to attention, proclaiming, “Yes sir, Drill Sergeant, sir!”

It was a declaration that caused the old man’s heart to swell.

His son—his own flesh and blood—possessed the ability to maim and wound and return honor to the Confederate States of America.

“Then affix bayonet, dear child!”

Junior attached the metal blade to the end of a rifle with the diligence and skill of a well-trained soldier under the command of General Thomas Jonathan Stonewall Jackson—God rest his soul and bless him.

The Confederate cared deeply for his son, proving it each time they went hunting in the woods. When their stalking ended in gunfire, it was Junior’s shot that broke the soundless forest first. The Confederate resisted his itchy finger, only indulging in the safety shot after his son’s barrel was already cleared. Junior—still young and not yet calloused by war—often missed, and it was The Confederate’s shot that typically downed the deer. As it fell, its knobby legs crumpled to the vegetation first while the remainder of its heft toppled after.

“Affix bayonet?” Junior asked innocently after each kill. While his father fully appreciated the gusto with which his son slaughtered, he had to deny the request.

“Sorry, pal,” he’d say, clapping a hand to his son’s shoulder, “Think this one’s already dead.”

The Confederate had a wife, a maker of time machines. She was a stay-at-home-scientist whose paychecks were stamped with the insignia of Vanderbilt University though her work received private funding from blackout groups within the deepest bowels of the government.

When asked what she did for a living, The Confederate declared, “She’s a Yankee sympathizer!” which wasn’t exactly true though he thought it accurate enough.

He had convinced himself that his wife’s interest in overcoming barriers of the time-space continuum would inevitably benefit the North.

But Charlie, don’t you see?” his wife argued. “It would benefit the entire country. It would allow us the privilege of foresight.”

“Oh Lynda,” he chuckled, shaking his head. “That’s all well and good, sweetie, but you’ve forgotten about hindsight, love. Has anyone ever stopped to consider hindsight for crying out loud?”

In the early years of their marriage, he’d obsessed over her work, causing her to wonder if that’s where the attraction lay.

“So allow me to clarify,” he’d say, clearing his throat. “Time travel goes both ways, correct? I mean, let’s say I want to go to the Battle of Fredericksburg, but later, I wanted to jump to…I don’t know, the Battle of Vicksburg. Then on to some future battle that hasn’t even happened yet. Something with lasers. Lasers versus Robots. Could I do that? Could I go to the Lasers versus Robots war directly from the Battle of Antietam? From a scientific perspective, I mean. What are the odds of that happening?”

“Well…technically, sure,” his wife conceded. “That’s our great hope. That we might correct the errors of the past while simultaneously testing out the future.”

“Uh huh. Okay. So let’s say I have a hankering to go to Harper’s Ferry, but first, I want to pick up George Washington’s sword over at…”

Logic was not his strong suit though what he lacked in intellect he made up for with steadfast determination.

Once, many years back, under cover of darkness, he’d snuck into Chattanooga Military Park and gone to great lengths to remove a plaque proclaiming the sacred land a “Union victory.” A park ranger discovered him and hauled him to the county jail on two separate charges: trespassing and defacing public property.

“The crime here,” The Confederate spat as he was guided into the backseat of the squad car, “is you thinking I’ve done something wrong. I’m setting the record straight, goddamnit.”

After receiving a written warning and a light slap on the wrist, he was released the following morning, all charges dropped, provided he never again set foot in the park.

“I promise,” he saluted. “Scout’s honor.”

However, by the following evening, his steadfast determination overpowered his promise. He returned to the park, completing his mission without further interruption.

At midnight, from atop a silent bluff, he threw the plaque into the mighty Chattanooga. The rushing water washed away what it couldn’t erase completely.

The Confederate didn’t consider himself one of those “Civil War eccentrics,” one of those “live-in-the-past” kind of guys. After all, his home contained all the necessary accoutrements of a well furbished, modern home.

Running water in every sink.

Electricity.

They even had a computer with Internet access though The Confederate found this particular luxury excessive.

Yet despite technology’s intrusion, theirs was a happy home. In the evenings, when he returned from his job as a grounds crewman at the local high school, he was often greeted by his son’s attempts at recreating historically accurate representations of key Civil War battles along their living room floor. Junior strategically set-up his plastic green soldiers along the ridgeline of the couch, continually revising their formations.

But on returning home one August afternoon—hands still reverberating from the shakes of the mower, shoelaces dyed green—he was surprised to find Junior positioning his men along the dinner table instead. Far below, the Yankees remained scattered on the carpet.

“If that’s supposed to be the Battle of Ball’s Bluff, then your scale’s all wrong,” The Confederate warned. “How many feet to an inch, do you figure?” He squatted beside his son, eyeballing it. “I’d give it about ten feet per inch. Sound about right?”

“Huh?” Junior asked, noticing his father’s presence for the first time.

“Ball’s Bluff,” The Confederate repeated. “You know.”

“What about it?”

“That’s the battle you got going here, right?” he asked, fiddling with the men. “You got your Confederates here, driving the Yankees over the bluff right here, and this down here’s the Potomac. It’s all pretty good, Junior. Just your scale’s off. We can fix that.”

Junior shook his head.

“It’s not Ball’s Bluff. This is a battle you don’t yet know about.”

The Confederate clamped down on the insides of his cheeks, trying to keep from laughing.

“Oh reaaaaally,” he smiled. “Well by all means, enlighten me.”

“Well, for one thing, it’s a battle from the future,” Junior confided, still fiddling with his men.

“Says who?”

“Says Mom. She saw it. When she went there.”

The Confederate’s smug smile dissipated. He pushed on his knees and rose, tearing toward the bedroom.

“Lynda!”

“Shh, she’s sleeping. She’s tired now. From all that traveling.”

“Lynda,” he called even louder. “You in here? You in here, love?” He swung the bedroom door wide, spying her pale, bare feet on the carpet beside the bed.

“Lynda!” he said, running to her.

She stared up at him with empty eyes. Sweat dampened the top of her blouse. Her legs remained exposed above the knee. An array of different colored sensors remained suction-cupped to her forehead, their wires snaking to what appeared to be a small, metallic shoebox. She shuddered, and one by one, he pulled the sensors off and placed a hand to her forehead.

“You’re freezing,” he whispered. “Jesus, why are you freezing like that?” She gasped, trying to allow the words to croak from her throat.

“I’ve seen the future,” she whispered.

“And?”

She squeezed both hands tight on his wrist.

“It is not…good.”

“Mommy, was I there?” Junior interrupted, smiling from the doorway.

Shuddering, his mother nodded sadly before closing her eyes.

“Yes, sweetie. That was the worst part.”

The Confederate had a hobby.

When time allowed, he enjoyed noodling in the open waters of the Cumberland River. He was well practiced, and after years of refinement, had become quite the proficient noodler. It required little skill: simply mustering the courage to dangle an arm into the freezing river, then waiting for something to bite. Typically, the “something” was a gigantic catfish of impossible size, its whiskers miniature whips, its razor-sharp teeth two-dozen reminders why one should never attempt to go noodling. Still, it was an enjoyable pastime—something that reminded him of his childhood—and a tradition he looked forward to passing on to his son.

“So…what do we do exactly?” Junior asked. They tromped through the wilderness in coonskin caps and deer-hide pants. This, The Confederate said, was to help maintain a certain level of authenticity.

“Well, the first thing you gotta do is block your mind of fear.”

“Okay,” Junior nodded, blinking twice. “Now what?”

“You’re already done blocking your mind of fear, kiddo?”

“Uh huh. I did it a long time ago.”

The Confederate raised his eyebrows.

“So next you’ll want to hunt for a good part of the river, some place that doesn’t flow too quickly.”

They found a place sequestered between a rocky embankment and a few downed limbs. Father and son—careful not to let their coonskin cap tails fall into the water—lay flat on their bellies and stared hard into the stream.

“Now you want to get yourself mentally prepared. And it’s not as easy as it looks. But once you are…”

The Confederate took a few seconds to close his eyes and breathe deep. His heavy exhales caused his beard to waver.

“But once you are,” he repeated, “you dunk your arm in, all the way up to the shoulder, you see.” He demonstrated, the cold creeping through him, the low, slow ache pulsing from his fingertips to his elbow.

“Then what?”

“Well, then you wait.”

A moment passed and the cold water entered his bones. The Confederate gritted his teeth and tried to block out the cold.

Junior looked hard at the ground, staring at an anthill.

“How you feeling, kid?” The Confederate chattered. “Brave?”

“Pretty brave, I guess.”

“Okay, then you’ll want to go ahead and put your arm in beside mine. You’ll adjust to the temperature.”

Junior considered it, eventually closing his eyes and imitating his father’s heavy breathing. The breaths continued, growing noisily, and finally, after much fanfare, Junior opened his eyes once more and said, “Could I just affix a bayonet instead?”

“No, sir,” The Confederate chuckled. “Not for noodling. No bayonets required.”

Junior paused. He peered down.

“So what’s down there anyway? Like, fish?”

“Well, sure, some fish, I’d imagine.”

“How about snakes?”

“Sure. That’s possible.”

Junior paused once more before continuing.

“Are there skeletons down there, do you think?”

The Confederate smiled.

“Well sure, pal, probably a few Yanks. But they’re not gonna bother you. We killed’em a long time ago,” The Confederate winked. “You can thank your forefathers for that.”

Junior moved hesitantly toward the river, his shaky hand tapping the top layer of water, his skin sticking from the wetness. He inched deeper, his entire arm suddenly plunging into the heart of the river.

“Good!” The Confederate cried. “That’s the spirit! Just like that.”

Junior trembled, wincing and keeping his eyes closed tight. The Confederate heard a low humming escape from somewhere within his son’s chest. A war cry, perhaps. Or a whimper.

“Hey, come on now. Time to be a man,” The Confederate said. “Besides, if these fish have any sense in’em, they’ll go for the bigger bait.”

The Confederate bulged his bicep underwater, made himself the bigger bait.

On the days when Lynda required peace and quiet for her work, The Confederate and his son practiced drill commands in the yard. The house freshly silent, she retreated to the shallows of a mildewed basement, reexamining the structural integrity of her lines, the insulative power of the wires and connectors.

Meanwhile, father and son fit themselves snugly into britches and wielded guns. Powerful guns. The kind that didn’t allow for mistakes.

They marched, their rifles tucked tight alongside shoulders, their chests thrust out like peacocks.

“Present, arms!”

Junior attempted a rifle salute until his father allowed him to stop.

“Order, arms!”

They marched a bit more, boots clomping in the flower garden, displacing the mulch and the bulbs while the neighbors watched on from their windows.

“About, face!”

Junior turned 180 degrees, erect and silent.

“Forward, march!”

The Confederate smiled as his son responded to each and every command. He knew he could continue the orders for the remainder of the morning without complaint.

Much to his father’s surprise, Junior’s small frame managed the weight of the gun quite nicely. His childish chest carved hollows along the ridge of his stomach each time he inhaled, and the gun managed to fit in the space.

After drill, the pair collapsed beneath an oak in the backyard, sipping orange Gatorade, cooling their bodies and restoring their electrolytes in the swelter of the shade. The Confederate had a stick in his left hand and busied himself drawing schematics in the dirt surrounding the tree.

“So what General Beauregard did was, he moved his troops north of Shiloh, like this.” He drew various x’s into the dirt. “See, what Beauregard knew that Grant didn’t was that the terrain was highly vulnerable to sneak attacks. So that’s what they did. Old Beauregard pushed the Yanks back to the Tennessee River, right here, when all of the sudden…”

“Wait…so we won?”

“Jesus, kid, I’m trying to tell you the story.”

“Well, we must have won, right? Because of Beauregard’s fine leadership and the cowardice of the Union army?”

“Well, that’s how it should’ve happened. Most historians chalked it up a loss for the good guys, but most of those historians are piss poor Northerners anyway so you kind of have to take what they say with a grain of…”

“Dad,” Junior squinted, picking dirt from beneath his nails. “Did we win any of those battles?”

“Well, sure! Ever hear of a little something called The Battle of Chickamauga? Fort Pillow? Paducah and Petersburg? And then you got your Battle of Poison Spring, of course…”

“So why didn’t we win the war?”

“Christ, don’t they teach you anything in school?”

Junior shrugged.

The Confederate explained it the way his father had explained it to him.

“It’s like this,” he sighed, motioning with his hands. “The winners and losers all depend on who the hell’s telling the story. Make sense?”

Shrugging, Junior dusted himself off, then moved toward the kitchen to refill his glass with Gatorade.

As the summer wound down—after their talk beneath the shady oak—The Confederate found his son’s zeal for southern independence had begun to falter.

“Want to drill?” he’d ask, though by the fall of the year, Junior’s shrugs had turned into no’s.

“Well why the hell not?”

“Homework,” he’d explain. “Ms. Henson’s sort of a bear about it.”

The Confederate tried hard not to take the rebuffs personally. Homework was important, after all. Occasionally, he’d catch Lynda nodding at Junior’s response, as if approving his responsible decision.

“You don’t have to encourage him, you know,” he told her one night in bed.

“Encourage him to do what?”

“To not drill with me.”

Lynda’s eyes were closed, her hands on the cool side of the pillow.

“Honey, I just think that maybe your...reverence for the past hasn’t quite rubbed him the same way.”

“Sometimes I don’t think it’s rubbed him at all,” he grunted.

“Why do you think that is?”

“Cuz he figures we’re a bunch of losers.”

“Why would he think that?”

“How the hell should I know? He probably thinks all we ever do is lose battles.”

“Well, the Confederacy did lose quite a few…”

“We,” he pressed, rocking her shoulder, “we lost quite a few, Lynda.”

“I didn’t lose anything.”

The Confederate murmured.

The Confederate changed the subject.

“How’s that time machine coming?”

“Fine.”

“Is it really?”

“Sure. I figured out one of the problems. The initial readings didn’t account for gravitational pull so when you take that into consideration…well, never mind, it gets sort of theoretical.”

“That’s okay. I like theoretical.”

She sighed.

“So I had to account for it, Charlie. That’s all.”

He nodded, tucking himself deeper beneath the covers and flicking off the light.

“Well don’t forget to carry the one, hon,” he smiled.

He kissed her cheek, and they turned quiet together.

A moment later, he broke the silence.

“It’s going to work, then?” he asked.

“Sure, one of these days.”

“And it’s going to show us a bright future?”

She yawned, nodding.

He smiled, breathing in her scents: freshly laundered sheets, pinecones from just outside the window.

“I think tomorrow Junior and I are going to spend some time in the woods,” he announced.

“That sounds nice.”

“We don’t even have to play Civil War if he doesn’t want to. We can just walk. Hike. Enjoy our surroundings.”

“I think he’ll like that.”

“Well, he damn well better,” The Confederate scoffed. “What kid doesn’t like the woods?”

That night, The Confederate dreamed of bugles and drum lines and an entire cavalry of sneering, dust-clouded horses. The men atop them were painted gray, swords drawn, glistening. One of them, a ghost soldier, cantered away from the others, pulling his reins just inches from The Confederate’s dreaming face.

“What…what do you want?” The Confederate mumbled in his sleep.

The ghost soldier cleared his throat and then, quite robustly, broke into song:

O, I wish I was in Dixie!

Hooray! Hooray!

In DixieLand I'll take my stand,

To Live and Die in Dixie!

He saluted before trotting off into somebody else’s dream.

In the morning, when The Confederate woke, he found himself humming the tune.

“It’s kind of nice,” Junior told him, “not having to wear the deer hides and all. Or the britches. It’s a lot cooler without the britches.”

The Confederate nodded.

All around them, the woods were alive with animals. Already they’d spotted two white-tailed deer and a fox, and each time, instinctually, The Confederate lifted his arms as if attempting to fire a gun he wasn’t holding.

“Affix bayonet?” Junior joked, and they shared a good laugh from the old days.

That morning they viewed nature in a different way—something to treasure, something worth preserving. They even paid notice to the mockingbirds and irises that followed them along their path.

The Confederate identified what he could—coralberry, bluebells, the Virginia willows—and much to his surprise, Junior seemed enraptured by his knowledge.

“So can you just plant them anywhere?” he asked of the wood sunflower, to which his father replied, “Well, they tend to flourish best in damp climates. Need a helluva lot of rain and sun to make it much past August…”

In the dead of October most of the flowers had already sunk their heavy heads. But The Confederate and Junior paid close attention to the ones that remained, brushing their fingertips along the petals as if renewing them with life.

“Noodling?” Junior suggested upon reaching the river. The Confederate was only too happy to oblige.

Several weeks had passed since their last attempt, and while Junior had yet to receive so much as a nibble, The Confederate had felt the sinking teeth dig into his flesh on more than a few occasions.

The Confederate lay belly down along the bank and rolled up his sleeve.

“Shall we?”

Junior smiled, matching his father’s motions.

They lay there, their backs warming in sunlight, the trees gathering shadows and cooling them in the dark, dappled patches of skin.

As they noodled, they discussed Ms. Henson’s insistence on weekly vocabulary tests, how she deemed reading, writing and mathematics far more important than social studies.

“But social studies is the keystone to everything!” The Confederate argued. “Jesus Christ! Who in their right mind would choose, actually choose, to gloss over the events that made our country what it is today? Take the War of Northern Aggression, for instance…”

“I know! That’s what I told her!” Junior argued, “But she said…”

In mid-sentence, the fish rose up and latched onto Junior’s arm. Junior screamed, helpless, as the gigantic gold-flecked beast dragged the boy into the river, down the river, and within moments, beneath the river too.

“Son!” The Confederate called, jumping to his feet. “Junior!”

He dove into the cool current to search.

But ten minutes later, his frantic searching yielded little: driftwood, a rusted bobber, some tangled fishing line. And twenty minutes later, when he discovered his son’s weed-wrapped body clinging to the shore—bite marks beyond the elbow—the search abruptly ended.

Far off, he heard what sounded like the canter of a ghost horse. He wept in the clay on the banks of the shore. He called for help. Only his echo called back.

They buried what they couldn’t bring back. Buried him deep, in a coffin, in the ground, in the cemetery.

To the outside world, their grief appeared surprisingly short-lived: the result of propelling themselves headlong into their respective professional lives. Lynda’s time travel productivity increased two-fold, and when The Confederate woke in the morning, he found the bed empty and cooling beside him. And at the end of the day, after brushing his teeth and returning once more to the bed, still, her space retained the empty shape she left him.

Almost nightly, he heard her clomping up the stairs—sometimes in the purple dawn of the morning—her face red, her hair clumped and matted.

Her hands were often stained chalk white from calculations, and when he asked about her findings, she’d pinch the top of her nose and close her eyes tight and say she had a terrible headache.

Some nights they slept, some nights they didn’t. But each morning he’d wake to find her missing. And twenty minutes later, after coffee and toast and a shout goodbye down the basement steps, he too returned to work.

There were dying flowers to unearth, weeds that needed uprooted.

The recurring dreams were too much for him. Too many gray horsemen. Too many bridles. Too many metal bits worked between the teeth of the horses’ uncooperative mouths.

Always, he’d wake humming the same damn song, until eventually even sleep became a luxury he could no longer seem to afford.

So instead of sleep, he drilled.

He drilled in the backyard in the nighttime. Drilled by the riverbed. Drilled by the trees. He drilled, kicking his feet and snapping his shoulders back, his movements amplified in shadow. Some nights, when he was brash and sleep-deprived, he stopped drilling long enough to plunge his arm into the cold heart of the river. Revenge was a word he understood and a concept he fully grasped. While the golden fish never returned, never dared a larger meal, it didn’t stop The Confederate from trying.

“Come on, Yankee scum,” he baited, “why doncha give this arm a try?”

The Confederate, a good soldier himself, remained steadfast and determined. And when the river offered nothing, he had no choice but to return once more to the yard, to the oak that had long since stopped growing, to the grass in need of a cut.

When he drilled, he wore his finest confederate attire—a brass buttoned gray coat, dark britches, a belt buckle with CSA stamped on the front. A sword dangled from his left hip, and he carried a rusted rifle.

“Slow march,” he huffed to himself. “Slow march.” And then, when he quickened his pace: “Quick march, soldier, quick march!”

The sweat, even in the cool night, drizzled down his forehead. The trees, he discovered, lost their leaves in the darkest hours when no one else was awake to witness.

“To the front!” he demanded.

“Change step!”

“About face!”

The gun felt light in his hand, and the sword, weightless.

When Lynda saw him there, marching in moonlight, she stayed quiet. From the screen door, she watched as he ordered, “Mark time! Mark time!” again and again, his knees kicking parallel to the ground.

“Mark time! Mark time, soldier! Mark time, goddamn you!”

“Charlie,” she whispered, slipping out the screen door. “Honey, are you okay?” Oblivious, she stepped on the Welcome mat, restarting the tune from his dream.

She stepped forward, but the song repeated, music blips drifting out from the mat. She moved to the grass.

“Honey…”

“Mark time! Mark time! Soldier, mark time!” he called, overpowering “Dixie,” searching once more for his gait beyond the music.

“Darling…”

“Mark time! About face! Mark time!”

“Shhh…just stop, Soldier.”

The Welcome mat turned quiet.

She put his hands on his shoulders and said, “It’s time for you to just stop now. Please.” He peered into the black woods, refusing to face her.

“You know,” she began, picking the lint from his jacket, “you look quite heroic in uniform.”

“Mark time,” he sighed miserably.

“Yes, I know. We will.”

She touched his shoulders.

“Are you cold?”

“Naw.”

“Want me to top off the canteen?”

“No, I don’t think so.”

Suddenly, he tilted his ear to the wind. He held up one finger.

“The Yankees are coming.”

“No, they’re all gone now. You know that.”

He nodded, disappointed.

Finally, he turned to her.

“How’s your work? Are we there yet?”

“Eh. Getting there. I made some progress tonight.”

“March quick, soldier,” he begged her, his hands on her shoulders. “March quick.”

“Yes, I know, darling, I’m trying.”

His lip trembled. He reached for his canteen and drew deep from the metal container. He wiped his dripping face with his forearm.

“How long, Lynda, till it’s finished?”

She stared at him, her husband, his hands shaking against his sword.

She could not give him the answer he deserved, the one he’d been waiting for.

“Well, soldier,” she said, looking down at his boots, “how far are you willing to march?”

© 2009 B.J. Hollars

This story may not be archived, reproduced or distributed further without the author's express permission. Please see our conditions of use.

The Barcelona Review is a registered non-profit organization

B.J. Hollars is an MFA candidate at the University of Alabama where he's served as nonfiction editor and assistant fiction editor for Black Warrior Review. He is also the editor of You Must Be This Tall To Ride published by Writer's Digest Books. He has published or has work forthcoming in Barrelhouse, Mid-American Review, Hayden's Ferry Review, The Southeast Review, DIAGRAM, Fugue, and The Bellingham Review among others; he has twice been nominated for Pushcart Prizes.

B.J. Hollars is an MFA candidate at the University of Alabama where he's served as nonfiction editor and assistant fiction editor for Black Warrior Review. He is also the editor of You Must Be This Tall To Ride published by Writer's Digest Books. He has published or has work forthcoming in Barrelhouse, Mid-American Review, Hayden's Ferry Review, The Southeast Review, DIAGRAM, Fugue, and The Bellingham Review among others; he has twice been nominated for Pushcart Prizes.

Contact the author